Coming from Israel, where the genre of biography is much less popular, almost nonexistent, in comparison with the phenomenon in the United States, I feel that my role in this conference is to raise some suspicion concerning the validity, autonomy, or originality of these genres. This suspicion is especially important at a time when biographies have become a modern form of hagiography. Biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs are perceived as “exemplary” stories with which both the writer and the reader are supposed to identify. Stories that arouse envy or awe of “remarkable” lives that transcend or transgress the ordinary and anonymous. Lessons of how to lead a life by certain power, by certain achievement – moral, spiritual, material – as revealed through the life stories of literary figures, celebrities, criminals, or tycoons. Even a television advertisement for Coca-Cola is a mini-biography, a hagiography of those beautiful modern saints on the screen. They show us what “the taste of life” is, and we are called to believe them and consume their advertised promise. This power of exemplary “life stories” that teach us, that tell us “how to live,” is an ancient tool in propagating power systems – religious, ideological, political, or commercial – systems that demand our suspicion and resistance.

Therefore, I’ll put forward some questions about biography, asking what is written first – the “bio” or the “graph”? Does life precede the writing of the life story? Or does the story precede life, shape it in advance, and dictate it? And who writes, who creates the story – the person who lives it, the one who writes it? Or perhaps the story writes us all. In other words, life is replete with all the incongruity of messy details and phenomena, and writing is a shaping skill with its laws and considerations. When we write a biography, an autobiography, or a fictional auto-bio-graphy, according to what laws do we fashion it, do we carve it? And what is its “plot”? For me the plot is the bones’ X-ray of the life story, the hidden vein that feeds both the biographer and the subject of the biography. Is the plot unique, original, or is there a preexisting plot, dominating the way a life story is both lived and told?

I’ve chosen an extreme case of biography to share my point with you. It might be a little unusual to call it “biography”; but from my point of view, not only does it meet the requirements of the genre, but this “generic” biography also shapes the basic plot underlying the Western story. The case I refer to is what I would name the Jewish Case, or the Jewish Biography, with its extreme forms of plot and personification, its singular timeline, and its unique modes of self-suspicion, up to the questioning of the whole status of the story. Today I’ll limit my reading to the overt, literal level.

From rising in the morning to the moment of falling asleep at night, from birth to death and burial, the myriad of gestures, thoughts, and even intentions are pre-articulated, forming a specific mold into which the particular life is poured. The private life in a given historical moment is a personal variation on that generic mold; always seemingly only a re-enactment – not an “invention” – of a preexisting role in an ongoing plot that started with Abraham, the first Jew, and is still unfolding.

The “Jewish Biography” starts and is projected into the future by the power of God’s Promise to Abraham. God chooses and extracts Abraham out of his life, sending him on a journey towards a new life, and a new place; a journey which is at once private and communal, unfolding and shaping through history. A projected biography that embraces, in advance, all future Jewish lives.

In fact, a Jew is born into an already articulated biography. In the traditional context of Halacha – the Jewish Law (which until two hundred years ago was the only way a Jew could define him or herself) – a Jew’s life is codified to a unique extent. From rising in the morning to the moment of falling asleep at night, from birth to death and burial, the myriad of gestures, thoughts, and even intentions are pre-articulated, forming a specific mold into which the particular life is poured. The private life in a given historical moment is a personal variation on that generic mold; always seemingly only a re-enactment – not an “invention” – of a preexisting role in an ongoing plot that started with Abraham, the first Jew, and is still unfolding.

The beginning of such a long and complex story could not be a trifling move. And actually, the delivering of God’s choice and promise required a few drafts, and a number of new starts, clearly seen in the biblical text. As if the Torah, like later the Talmud, the Midrash, and the rabbinical interpretations, were not only writing this Biography, but were exposing, from within, its difficulty of being, its fragility and explosiveness. In Genesis, God’s Promise is delivered a few times. Reality does not seem to follow it. In Genesis 15, three full chapters after the initial choice and Promise, nothing happens according to the projected plot. After arriving in Canaan, Abraham and Sarah are still childless, and they have already endured a war and a first exile. They are far from being settled as the ancestors of a promised nation in a Promised Land.

Why doesn’t life play out according to promised biography? Was the Promise flawed? Are these hardships a secret feature of this singular promise? Jewish commentators linger on these questions. But we can see that at this point, when Abraham himself starts to have doubts, a dramatic gesture is needed in order to straighten things out and save the Biography. In a highly theatrical, almost Hollywood scene with lavish use of special effects, God repeats his promise of the “covenant between the pieces.” A big show with fire and smoke and the bloody corpses of cut animals is displayed, night and fire descend, and Abraham falls asleep. At that moment God renews His promise – this time with many more details. In a way, He delivers to Abraham the Jewish Biography in capsula:

And He brought him abroad, and said, Look now toward heaven, and tell the stars, if thou be able to number them: and He said unto him, So shall thy seed be…And He said unto Abram, Know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they shall afflict them four hundred years; And also that nation, whom they shall serve, will I judge: and afterward shall they come out with great substance…In the same day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying, Unto thy seed have I given this land, from the river of Egypt unto the great river of Euphrates.

Gen. 15, 4-18

Now, we – God, the redactor, the involved characters, and the future Jewish people – are bound within a written-in-advance biography, with many obligatory stages, involving other nations and disputed borders. Amid some more complications, the story is going to follow this outlined plot, which can raise fresh suspicion: Was the Promise edited later, according to future events, by the redactor of the Bible and spliced here, in a way that reality will seem to fulfill it? Or does God’s promise impose its trenchant rules on the complexity of reality and human passions? Is this extreme – almost manic – case of Biography projected by a promise, a prison, an inescapable destiny? One of the great lessons this case teaches us is the subversive ways in which the Jewish tradition reads the Promise. This is a unique mixture of reverence and irony, of belief and resistance, and, above all, of an extraordinary human freedom; the freedom to participate in the creation of the story – an outrageous humanistic attitude that runs under much rabbinical thought, and is enacted through the re-articulation of the story. This, for me, is an essential feature of the Jewish Biography.

Let us stay with the unfolding of the Biography, through the selection of its designated lineage. After the late birth of Isaac (and there will be a lot to say about Sarah’s, as well as the other matriarchs’ initial sterility), the traumatic expulsion of Hagar and her son Ishmael follows. Isaac’s life, and with it the survival of the whole future Jewish Biography, is on the brink of extinction in the “binding of Isaac” (and the traditional commentators insist on the fragility and ambiguity of all the protagonists in this scene, including God and Satan). Yet, in the next generation, the choice of the lineage is even more dubious, as we have only one matriarch, Rebecca, who conceives twins. Bewildered, she reads God’s promise as a singular biography with only one inheritor, without any place for sharing, for plurality – a monotheistic story, with one God and one nation, immediately opening the abyss of jealousy and hatred, of dispute and fraternal conflicts.

And the children struggled together within her; and she said, if it be so, why am I thus? And she went to inquire of the Lord. And the Lord said unto her, Two nations are in thy womb, and two manner of people shall be separated from thy bowels: and the one people shall be stronger than the other people; and the elder shall serve the younger.

Gen. 25, 22-23

This is a unique mixture of reverence and irony, of belief and resistance, and, above all, of an extraordinary human freedom; the freedom to participate in the creation of the story – an outrageous humanistic attitude that runs under much rabbinical thought, and is enacted through the re-articulation of the story. This, for me, is an essential feature of the Jewish Biography.

Yet, in the generation of the twelve sons of Jacob the continuity of the Jewish “biography” is no less uncertain. Meanwhile, Jacob has been nominated “Israel,” so all of his descendants are part of the chosen nation-protagonist. No one can be excluded. Still, out of the twelve, the Jewish Biography follows Joseph’s fate. So, how is life going to follow it “naturally”? How will the family-nation be led into Egypt, “a land that is not theirs” for “four hundred years,” as God promised to Abraham?

Here the Midrash Tanchuma (Genesis, Va-Yeshev) gives a strikingly ironic reading. The Midrash starts by quoting a verse from Psalm 66-5: El norah alilah al b’nei Adam. Or, “In his work He is awesome toward the children of men, oh God.” And here we encounter a Hebrew word, which is a key word for me: alilah, meaning “deed” and “work,” but also “plot.” We can then read this verse: “In His plotting He is awesome toward the children of men, oh God.” Now, the term norah means “awesome” and “terrible” or “awful” so the verse can also be read: “In His plotting He is awful toward the children of men, oh God.” And echoing the Yom Kippur liturgy based on this verse: El norah alilah, I suggest it may be read “Oh, God of awesome plotting,” or even “Oh, God of awful plotting.” Following the verse, the Midrash interprets the outcome of Joseph’s story as the crude plotting of God. It is God who makes Joseph the hated sibling of his brothers, who finally plan to kill him, but alter their scheme at the last moment. They throw him in a well full of snakes and later sell him to a company of Ishmaelites, who carry Joseph along with them to Egypt. The Midrash compares God’s plotting to a husband who wants to divorce his wife. He comes home and tells her: “Serve me some tea.” She serves the tea. But, before even sipping it, the husband shouts: “This tea is lukewarm! How dare you serve me lukewarm tea. I’m going to divorce you.” And the wife argues: “You came home with a written divorce in your hands. So, why did you taunt me with this tea business?” Joseph’s prearranged exile is further compared in the Midrash to a farmer who wants his cow to plow a faraway field, but the cow doesn’t want to go out there. The farmer takes her calf and puts it in that distant field. The calf starts to cry, calling his mother. And, sure enough, the cow, hearing her calf, rushes to calm and feed him. Once the cow is there, she’ll plow that part of the field, as the farmer wished.

In a later part of the same section, the Midrash Tanchuma reminds us how strict the boundaries of the plotted story are. One step out of them and you are out of the story altogether. Joseph himself was at risk when his descent into Egypt went too far, according to the following Midrashic scene. At the moment he was being seduced by Potiphar’s wife, his father Jacob appeared before his eyes. Jacob showed him the twelve shining stones on the High Priest’s breastplate and said: “Do you see these twelve stones? They are for you and your brothers, and they are plated on the holiest of objects. If you are going to sleep with this woman, you are not going to have your stone among the twelve. You’ll be out of the story!” And the Midrash tells how, in fear of being left out of the story’s future boundaries, Joseph, who already had an erection, was poking his fingers into the ground, trying with all his might to hold himself back, to overcome his desire – an emblematic junction, characterizing both the imposing power of the story, and the power of its protagonist to choose to stay on within the promised Biography. Stepping out of it, either into oblivion or into another “heretic,” “deviating,” “truer” unfolding, is always possible, as it was in the case of Christianity, Islam, or other sects. I will not deal here with these “external” stories. I’ll just say briefly that not only the details of their “plots,” but the very status and nature of their story differ from the Jewish Biography.

Let us have another look at the term alilah, “plot.” In Hebrew as well as in English or in French (intrigue) the term means both the line of related events and a complot. In Hebrew, with its way of opening a thick field of contradicting subconscious meanings around the same root, alilah means “work of creation,” “deed,” “plot,” but also “slander” and “defamation.” The Hebrew expression “alilat dam”, literally “blood plotting,” means “blood libel.” Here language emphasizes the double-edged quality of any plot. It seemingly represents what happened, but in fact, we will never know what “really happened.” The subversive reading of the term “plot” in the Midrash reminds us that every story is the product of interested manipulation, that the very same “objective” data – facts, photographs, events, told with a different accent, can be turned into slander, defamation, a false accusation. It is precisely this abyss between controversial plots that dominates the history of tensions between the three monotheistic religions.

I am not going to tell you the full Jewish Biography with all its lavish scenes right now. For that we will have to sit here for a whole Passover Seder. So, I’ll skip a few thousand years and immediately zoom into the twentieth century. What happens to the plot and promise once the community distances itself from the purely religious terms? Does the Jewish Biography vanish, or is it articulated in other, secular forms? Who replaces God, “the plotter”? And how are the boundaries of the story redefined? I’ll follow the lives of my parents, representing two major trajectories of recent Jewish Biography.

My father’s family lived the Zionist story. Four generations went from the Ukraine to Palestine during the 1920s, all carried by another variation of the Zionist ideal, and with a deep belief that this constitutes the right and true unfolding of the Jewish Biography. My great-grandfather, Izik Hajies, was a pious Hassid, part of the group of “the mourners of Zion,” who on Sabbath afternoons would gather in the shtetl to lament the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. He immigrated to Jerusalem, to the ultra-orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim, carried by his mystical messianic longing.

The case is Jerusalem, a city that has been personified, and was given a biography – with a beginning, middle, and an aspired end. The problem is that the three monotheistic religions have articulated conflicting biographies of the same city, and that these disputing narratives are not confined to the fictional-mythical realm, but burst out into reality.

My grandfather, Mordechai Globman, was an enlightened orthodox Jew, who founded a modern Hebrew school in the shtetl, and was affiliated with the political movement of “Hovevei Zion” (the lovers of Zion). He settled in the center of Jerusalem, and was involved with the Zionist orthodox community. My father, Pinchas Govrin, his brothers, and his nephew, were secular “Poalei Zion” (the workers of Zion), pioneers, members of the “regiment of work” (Gdud Avodah) involved in the founding of kibbutzim, of drying the swamps in the Valley of Jezreel.

In spite of their different lifestyles, the four generations kept mutual respect and dialogue, united by a common dream. Inhabited with a deep sense of history, both my grandfather and father felt a responsibility to write their memoirs. My grandfather, whom I never met, started to write on his sixtieth birthday, in 1934: “Today is my birthday. I am sixty years old. Ten years ago, when I was fifty years old, I arrived in Palestine.” And then immediately, he moves into mythic language, saying: “I came down from the ship that carried me to Zion on my fiftieth birthday. And, as it is written ‘in the year of this Jubilee, ye shall return every man unto his possession’ so I, too, came back to my possession, on my fiftieth birthday, my Jubilee year.” Private biography is intimately lived through mythical terms. The personal and the collective persona are mingled in what he believed is the true, ancient biography. “These memoirs are a commemoration of our shtetl and the whole district of Wohlyn in the Ukraine, where Jewish life abounded.” He later gives a wonderful account of this life in the second half of the nineteenth century. “During these years the great move of immigration started. Most of our brethren went to the Goldene Medina [America] where there is no difference between a Jew and a Gentile, where there are only citizens, and one can live a private life. A small group chose to follow the promise of the prophets, and to go to Palestine. I will tell their story.”

Forty years later, in Tel Aviv, my father wrote his memoirs and was also interviewed at length for the Labor Movement’s archives. At the conclusion of his interview, he says: “If I had the choice to live my life again, I would live it in the same way, but with even greater intensity. We were all carried, leaders and simpletons, by the same great feeling of building a home for the Jewish nation. This has been the greatest creation of my whole life.” Once again, the private life, with its sorrows and joys, with the richness of details and events is lived as the fulfillment of a passionately expected culmination of the Jewish Biography.

Today, the Zionist chapter of the Jewish Biography could, certainly, gain from self-criticism and re-articulation, worthy of the Jewish tradition of multiple writing. Yet, the Zionist case also poignantly reminds us of how thin the line is between plot and slander, how much Biographies can arouse fascination and threat, jealousy, projection, and rejection. The perverted re-reading of Zionism by its opponents – labeling it “racism,” “colonialism,” etc. – is clearly a modern avatar of classical anti-Semitism, and its method of turning the Jewish Biography into narratives of heresy, blood libels, or complots of international conspiracy.

My mother’s story was shattered by the Holocaust. Many of my writings originate from her story. I’ll only briefly point to some of the questions the Holocaust poses for the Jewish Biography and to the genre of biography in general. My father’s family chose to be part of the Zionist story. The Holocaust demonstrates that there is not always a choice. It reminds us of the cases when there is no escape from the persecutions haunting the Jewish Biography; the cases when a Jewish identity is imposed by what Sartre called “le regard de l’autre,” the view of the other. You can convert, you can assimilate, you can deny any affiliation with this incredible meshugenah story, and then there is an event like the Holocaust. Three generations who already believed they were out of it, were caught and pushed back into the confines of the story, to their torture and death within the imposed ghetto of a “final” plot.

My mother, who lost her first husband and only son, survived the death camps. After the war she was a volunteer for the Zionist network working among displaced persons in Europe, and in 1948 she reached Palestine, accompanying a transport of children. She chose to articulate her private trauma as part of a national plot, leading from destruction to reconstruction and revival. On arrival she had cosmetic surgery to remove the number tattooed on her arm. Soon after she met my father, and they started a new life. Her decision – at least overtly, and for the first years – was to extract from her identity any trace of victimhood, any remnant of a former death camp inmate. Holocaust survivors who went to America, being out of a national Jewish story, sometimes took the Holocaust as the main event shaping their lives. Their children embraced the identity of “second-generation survivors” much earlier than their peers, of my generation, in Israel.

But the Holocaust raises questions about biographies beyond the Jewish arena. It reminds us of the alluring power of a story to attract, to seduce, like extraordinary biographies or hagiographies. It reminds us how the readers of such biographies are compelled to identify themselves with the protagonists, villains, saints, or martyrs. The fascinating and obscene spell of the Holocaust can arouse the desire to usurp this “irresistible” biography, to make it yours, to leave your ordinary life and to be “elevated” by this life of “saintly suffering.” Here I am referring to the case of Wilkomirski, and his less-known equals. The beatification of Edith Stein by the Roman Catholic church basically falls into the same category as a theological usurpation of the Holocaust story; usurpations which are no less ambiguous than the desire to reincarnate the Nazi “Satanic violence.”

In what plot should the Holocaust be told, be remembered? And how can its narrative be freed from its imposed, pre-written, obscene plot? And as for the Jewish Bio-Graphy, can it integrate this trauma without exploding? Can it re-articulate a mythical-theological story capable of addressing this event, of portraying its protagonists (including God)?

The last case from the Jewish Biography I discuss with trepidation, because of the recent political events in the Middle East. When I prepared this talk, I thought it would be just a thought-provoking example, but, in our region, the thin veil between the “bio” and the “graph” often disappears, and the events are quicker than their writing. The case is Jerusalem, a city that has been personified, and was given a biography – with a beginning, middle, and an aspired end. The problem is that the three monotheistic religions have articulated conflicting biographies of the same city, and that these disputing narratives are not confined to the fictional-mythical realm, but burst out into reality.

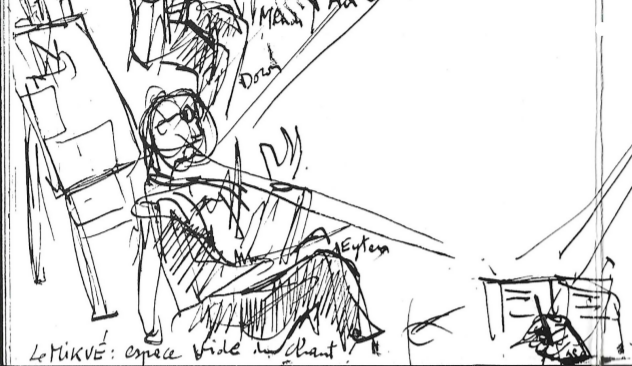

In 1990, Edith Kurzweil called me in Jerusalem and said, “Why don’t you write for Partisan Review about the first international poetry festival held in Jerusalem.” “Okay,” I said, and went out to the landscape, to see whether the place and the poetry can work off each other, deconstruct each other, give some breath to each other. I went with my own preconceived Jerusalem, like Paul Celan, like all of those pilgrims – Flaubert, Chateaubriand, Twain. Everyone comes to Jerusalem with a preconceived story of the city, which is a part of his or her cultural biography. Flaubert came to fuck Jerusalem, with a transgressional rage. Paul Celan experienced one of his only instants of erotic plenitude, just to lose it a moment later, falling into deception and tragic despair. Jerusalem, God’s bride, His place of desire, is always an erotic place, the place of masculine desire. Jerusalem is the biggest harlot of all places. The world’s cunt exposed on all the television screens, in an ongoing peep show, day and night. And yet, in the classical paradox of desire, everyone has his own Jerusalem, virginal and pure, defiled only by the others’ abusive and defamatory biographies of her.

I walked around the walls, climbing the Mount of Olives, where my great-grandfather is buried. According to my father, at my great-grandfather’s funeral my grandfather debated with the Chevra Kadisha, the mortuary people, until they reached an agreement, and the funeral went on. Later my father asked him, “What were you arguing about?” His father said,

You knew your grandfather, the pious Hassid. He wanted his grave to be directly facing the Gate of Mercy. Because when the Messiah will come he will enter Jerusalem through the Gate of Mercy. At that moment there will be so much havoc around, with all these people coming out of their graves. Your grandfather doesn’t want to be bothered with any of that. He just wants to stand up and walk directly to the Gate of Mercy. And as the mountain was turning here a little, I argued with the Chevra Kadisha that they dig the grave in a diagonal.

The plot of my great-grandfather’s biography was continuing after his death, and with a clear direction, so concrete that immediate arrangements could not be postponed.

The Gate of Mercy at the eastern side of the Temple Mount (Haram Al-Sharif), facing the Mount of Olives, has been blocked since the twelfth century, and for very similar reasons. The Muslims knew about the belief that the Messiah will enter Jerusalem through the Gate of Mercy. They took it very seriously, because legends, myths, projected biographies are the name of the game in Jerusalem. If there is a plot that the Messiah will enter through the Gate of Mercy, he is certainly going to do so, and very soon. It’s not a “Messianic” dream, it’s an imminent reality. He can come any moment. One can already hear his footfalls coming down from the Mount of Olives. So, the gate should be blocked with stones immediately. And for extra safety a Muslim graveyard was installed in front of it, because graveyards are considered impure by Jewish law, and therefore forbidden for priests.

Are these stories debated on the lawn of the White House? I’m afraid not. And what about the Christian, the Catholic, the Protestant, the American, the European biographies of Jerusalem? When will they be seen seriously as interested parties in the conflict, articulating the future of Jerusalem not only according to “objective,” “democratic,” “ethical” terminology, but through their own deeply rooted biographies of Jerusalem, with their own desired plots?

And what about the still-unheard female voice, the voice of Jerusalem? In writing about Jerusalem, I wanted to destabilize the traditional male voices, and their image of Jerusalem as the desired bride, the holy harlot, an image that has its root in the Bible and which is so embedded in Western culture up to nineteenth-century melodrama and literature. In my recent book The Name, in a subversive rewriting of a harsh accusation of Jerusalem delivered by Ezekiel (reclaiming this rabbinical gesture), I tried to give voice to Jerusalem, the tortured woman, the victim of slander, of false accusations. By an ironic perforation of the prophetic delirium, I tried to infiltrate the possibility of another plot, another multiple Biography.

Biographies exert a spell on their readers. They call for constant suspicion and breaking loose. This is how I understand the way Jewish tradition developed its unique techniques of writing and reading of the Jewish Biography; narrative techniques that are linear and nonlinear, an ongoing, multi-vocal debate which is palpable in the Talmud page, from its intimate texture to its layout – as if the Jewish textual legacy were saying: “Yes, there is one plot of one biography. Yet, there are so many ways it can and should be heard.” These interpreting, rewriting voices can be extreme, they can shatter the Biography, tear it apart, keep an ironic distance from it. Yet, in a paradoxical way, fidelity was deepened through this overt betrayal. And, by the inventive power of controversy, the complexity of meaning and of Text was renewed and multiplied. I’ll claim that this testifies to a distinct, original, subversive poetics. It balances human freedom – with its unreverential chutzpah – against “God the plotter,” in the ongoing writing of the Jewish Biography. This Jewish way reminds me of a joke about the Jew who was found on a deserted island after he was shipwrecked. Very proudly he showed his rescuers what he constructed: his hut, his oven, his shower. And then, he pointed to two additional small huts: “Here is a synagogue,” he said, “and here is another one.” The rescuers asked him, “Why do you need two synagogues?” And he answered, “This is the synagogue where I go to pray. And in that one, I’ll never set foot!”

Arguing, even within one’s self. In this sense I find a correlation between the Jewish poetic strategies and some of the great narrative devices. They are all writing and un-writing the plot, leaving the reader with a freedom of sight, untangling him from the hold of a hagiographic, fictional spell. I’m thinking of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu with its exposed waves of “new starts” brought about by the explosions of fresh, crucial intuitions. Beckett, who was a great student of Proust, shows in his early book, Proust, how, along this fictional autobiography, the plot is torn seven times, exposing the “backstage” of the present moment of writing, and providing a unique meditation on the incommensurable tension between life and plot. I think about Don DeLillo’s technique in Underworld, with his way of tearing apart and reconstructing the American Biography. These and other techniques provide us, I believe, with an indispensable, critical suspicion for writing or reading biographies, autobiographies, or fictional autobiographies.

I’ll conclude with a few lines from The Name, a novel or “fictional autobiography” of a second-generation Holocaust survivor. The main character and narrator, Amalia, is haunted by the biography of her father’s first wife, who died in the Holocaust, and who chases her like a dybbuk. Amalia and Jerusalem are juxtaposed in this novel, imprisoned in preconceived biographies, in historical or ritual plots. Through the last pages of The Name the narrative, the narrator, and Jerusalem are in a motion of opening, of ripening acceptance:’

As if a barrier was removed from the eye. The destruction exposed on the slopes, caustic, uncovered, as if this is the Covenant, and also the consolation. For there is no repair for the break. And there is no instant repentance. Only acceptance. What will be and what is and what was. Death here is consolation. The break hidden between us, King Who causes death and restores life. . .

Sabbath.

Ending The Name with the word Sabbath was for me a secret conversation with the poetic autobiography of Paul Celan. His last posthumous poem ends with the word Sabbath. Written during the six months after his only visit to Israel and Jerusalem, and before his suicide, this excruciating last cycle of poems echoes the sites of Jerusalem, trying to write his own poetic autobiography into the place and its biography. The attempt did not rescue Celan from his final despair. In an intimate whisper to Celan, The Name ends with Sabbath in a feminine voice, and in Jerusalem. And with hope, I hope.

Thank you.