Hebrew Translation: Mulli Meltzer

Adaptation and Directing by: Michal Govrin

Set and props: Doron Livne

Costumes and props: Anat Palenker

Lighting: Ben-Zion Munitz

Movement: Raffi Goldwasser

Poster & Programme Design: Raphi Etgar

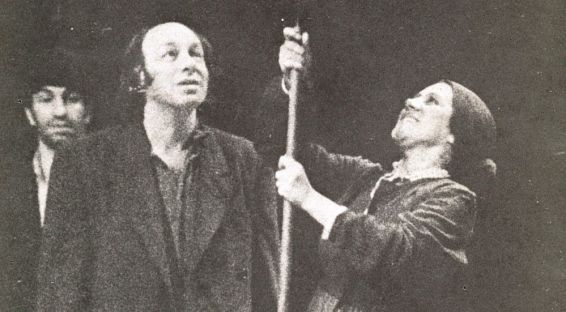

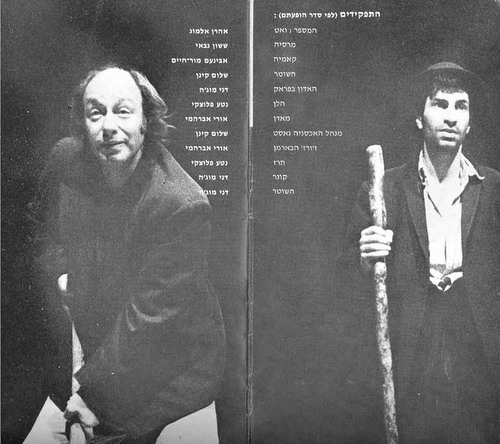

Cast:

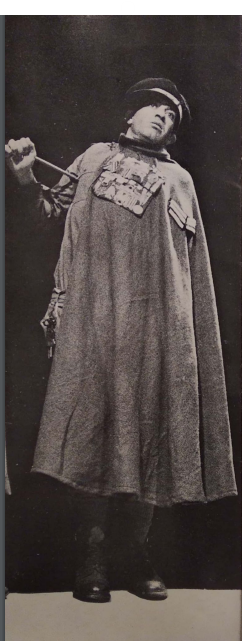

Narrator; Watt – Aaron Almog

Mercier – Sasson Gabbai

Camier – Avinoam Mor-Haim

Guard – Shalom Keinan

Gentleman in Park – Danni Mudja

Helen – Neta Plotzky

Madden – Uri Avrahami

Hostel manager Gahst – Shalom Keinan

George the Bartender – Uri Avrahami

Terez – Neta Plotzky

Koner – Danni Mudja

Policeman – Danni Mudja

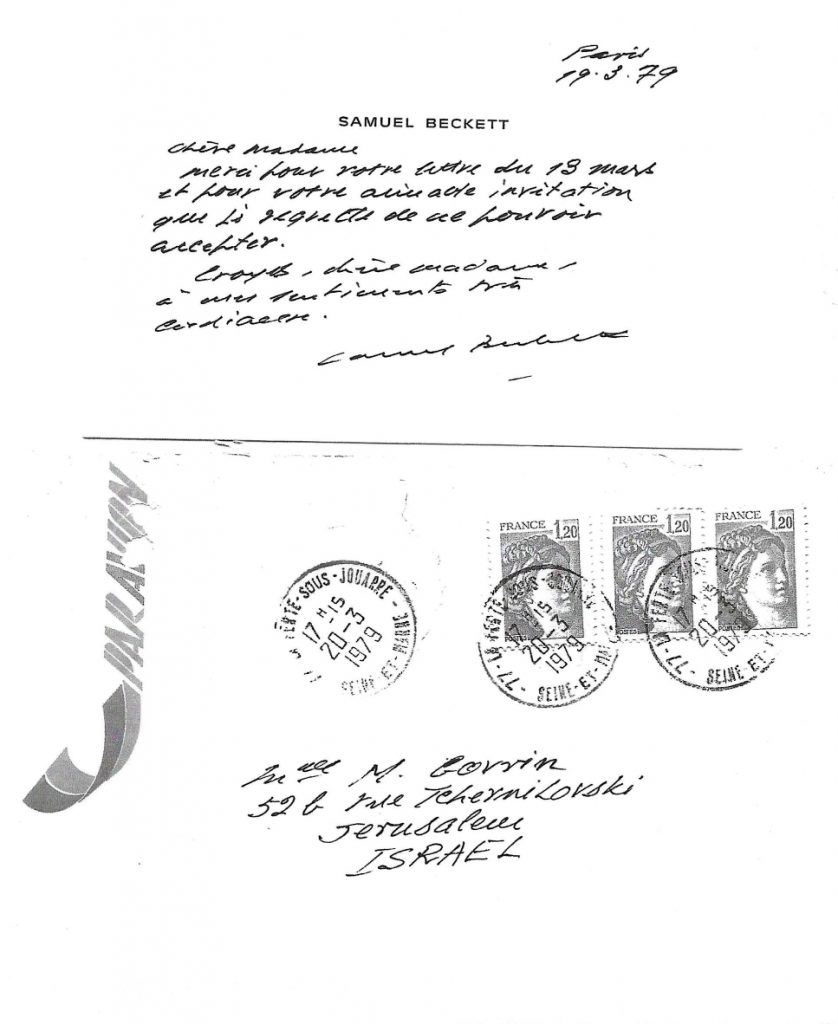

“Mercier and Camier” was written in the beginning of Samuel Beckett’s “French phase”, in 1946, two years before “Waiting for Godot” was written, but was only published in 1970. Beckett himself titled his book “a novel”, but in effect “Mercier and Camier” can be referred to as a hybrid, as it lies somewhere between a novel and a play. This is an interesting moment in Beckett’s literary development: up to that point Beckett considered himself to be first and foremost an author of prose, and it is true that in “Mercier and Camier” one can find the foundations of his mature prose, which reaches its perfection in the trilogy; yet it is equally true that in this book the theatrical components are just as evident as the prosaic ones.

The dialogues – between two characters or more – are built as “scenes”, and the precise descriptions of body movements and facial expressions literally demand that they would be translated into stage directions. In terms of abstraction, “Mercier and Camier” can be graded as the stage that precedes “Waiting for Godot”. In “Mercier and Camier” we know certain things about the lives of the main characters, and though they might be few and scattered, some details tie the location of the plot to a certain place, probably to Dublin and its suburbs. As “Vladimir and Estragon”, “Mercier and Camier” know as well that to truly live is not an option; the only possibility left is to pretend to be “living” until “this whole business is finally over”.

[Edited from “On Mercier and Camier” by Mulli Meltzer (the translator of the novel to Hebrew), in the programmer of “Mercier and Camier”]

The staging of the novel in the Jerusalem Khan attempts to emphasize the tension between Beckett’s two different styles of writing – the prose and the drama. Two plays occur simultaneously on the stage, one next to and depending on the other: one is Mercier and Camier’s journey that is full of hardships, the other is the monodrama of that “third person” that “was with them all the time”, that is present with them through the whole duration of the play, and that conducts a journey full of hardships in the cellars of his memories.

The materialization of this tension stresses the extent to which the narrator of Beckett’s differs from the traditional one. Beckett’s narrator is not omniscient, and he does not activate the characters; Mercier and Camier put their trust in their belongings, which grow fewer and fewer, while he clings onto words, words that will grow more and more fractured in the mouths of the narrators of Beckett’s future novels.

The narrator and Mercier and Camier go through a parallel process of decadence that reaches its pick where at the end of the play a full stop in movement is suggested: “But all day that is how it is, from the first tick to the last tack, or rather from the third to the antepenultimate, allowing for the time it needs, the tamtam within, to drum you back into the dream and drum you back out again. And in between all are heard, every millet grain that falls, you look behind and there you are, every day a little closer, all life a litter closer. Joy in saltspoonfuls, like water when it’s thirst you’re dying of, and a bonny little agony homeopathically distilled, what more can you ask?”

The story of the journey that slowly dies out, echoing back and forth between the narrator and the characters, as the movement of a pendulum that grows endlessly shorter – a movement so essential to Beckett’s world.

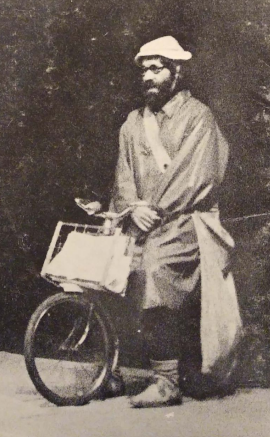

The movement was emphasized in this performance more than any other theatrical mean. At some points the words are only used as an external outline that accompanies the movements and demonstrates the vibrations of the mind. The emptiness of the stage and the essence of the movement influence the objects and the old clothing, to function as pieces of rudimentary life. The only instrumental accompaniment in the play is the sounds made by the steps of the characters, their voices, the moments of silence and the rhythm of movement, while the lighting that opens and closes the horizon above the course of the movement reflects the vibrations of the landscape, of the physical world, from which Mercier and Camier fail to escape in order to finally go out on their journey.

[Extract from: Michal Govrin, “About the Play”, in the programme of “Marcier and Camier”]