Introduction

“Exile” was read while on a journey. My journey vis-a-vis Frederic Brenner’s journey into Exile. And like every journey, at least on the surface, the sequence moves in a certain direction. Through space, time, and the events that take place then. From them, it sets sail on waves of memory to other times and places.

The present journey took place in August 2001. Since then, I have not made any changes to the text. Not even in light of events that took place afterward. I left the fragments of writing like a photo, taken with one single opening of the shutter. It is the eye of the reader or the observer that peels off the layers of the future from it.

*

At Passover 2001, in a Jerusalem cafe called “Parenthesis,” Frederic Brenner invited me on a journey to Exile, to “Egypt.” To relatives I hadn’t seen for a long time. He orders like an impresario, a kind of authorized emissary. Demands that I leave the refuge of Parenthesis – the lines of a poem, the distance, the view from the Women’s Section.

I’ve always had difficulties with relatives. Approach-avoidance issues with them. For fear of being swallowed up in the embrace of a relative-stranger, in the orbits of “Jewish” time, the rustle of beards and featherbeds and houses in “Exile” – “the fruit of their own loins absorbed without a trace”.1 And now too, I flinch: for the legends taught us that in the depths of Parenthesis a road without return is opened.

But maybe this time, I try to console myself, this will be a journey protected by a distance of album pages, without smells, or shouts, or invitations to weddings or bar mitzvahs. No, I admit, the distance is only a delusion. Because the anger overflowing in me against the frame of the photos imprisoning the faces looking out into a post-modern, promoted “Exile,” betrays a closeness I hadn’t imagined.

And on second thought, maybe the album is Frederic’s way of saying that “all Jews are responsible for one another”? His own way of gathering a kind of community, fragile, close and far?

*

And suddenly, the temptation to turn into a child again. To sit down with those aunts and uncles, whose existence I’ve almost forgotten, and who suddenly pop up as from a dream. To sit down with them in a corner of the room, in the alcove in Wadih Amlah. To suck in the smells, the tone of voice, what they tell with a gesture, with a pendulum ticktock of a clock, with the bottom of a pot where generations of women have stirred the kosher porridge.

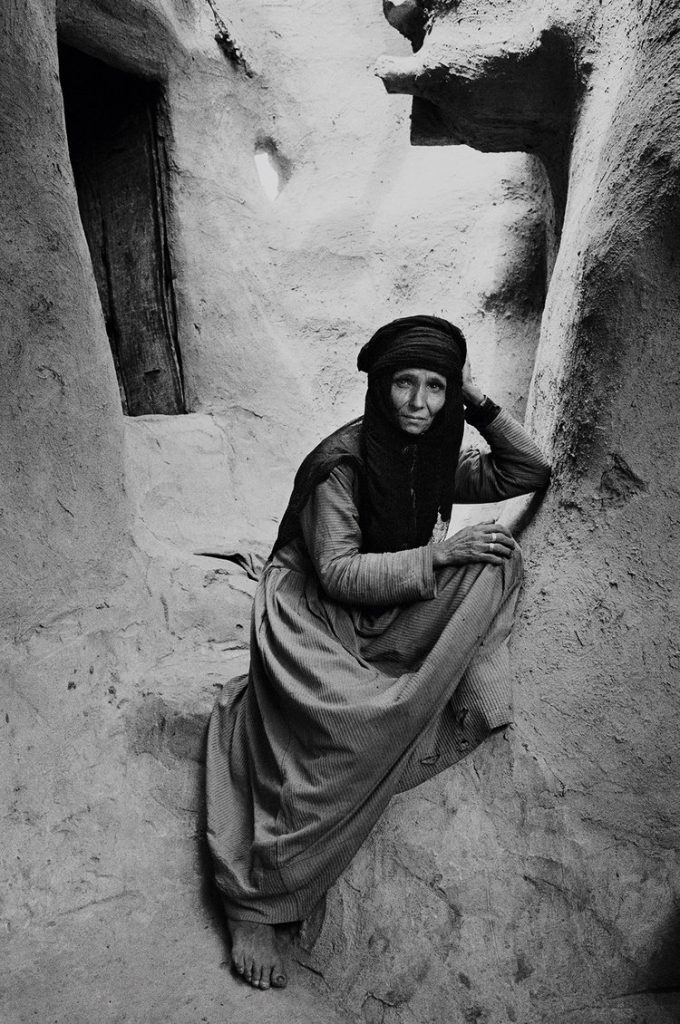

[1]

From the photo, the body of a woman with long hands and feet in the lap of an alcove approaches me. A graceful desert woman leaning the folds of her body on the wall. Giving herself from the distance. Reflecting on the camera from the transparent limit around her. Sheltering the recesses of her womb: Source of the nation.

The open and sheltered body of the woman – nameless – in Wadih Amlah.

I identify my movements in her. The relaxed body resting in front of the camera. My dark counterpart. Her voice plays in me with its throaty, strong tones, hushed groans, shouts of pleasure, of pain, chokings of joy.

Her clenched lips. “A woman’s voice is a sexual temptation.” The voice of sexual temptation in which the Women’s Talmud was written.

She lifts her eyes, like Rachel who refuses to be comforted.

Her foot is ready to take a step.

Her beautiful hands, hewn in toil, grip me, send me on a journey.

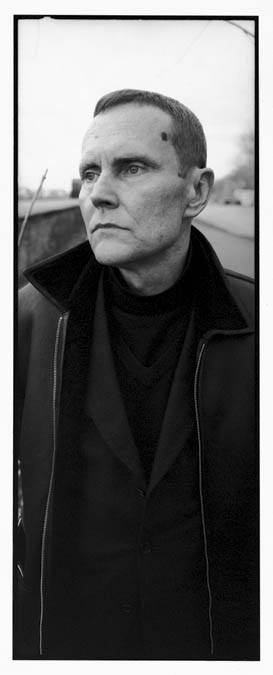

[2]

the photo of Germany/Berlin

(August 8, 2001. On the plane. On the way to Australia, to book festivals, sent by the Israeli Foreign Ministry. Seventeen hours of dark hovering to the end of the night. On that journey I took the chronicle of photos of “Exile.”)

Receding Image of Father and Mother on the Train Platform in Hanover

The same suitcases, the same trains

Carrying the light of the engine and cigarette smoke into the nightDark falls into dark

So transparent they stood in the station

And abysses of death overflow their banksHow will I again take hold of the handles of my travel bags

From “That Very Hour.”

Translated from the Hebrew by the author, with Peter Cole; Partisan Review, April 2001.

“A late picture outside the collection,” Frederic tells me. Beyond the iron curtain of repression. In our hasty conversation in Parenthesis, I don’t recall what he told me, who is that man who averts his eyes from the camera. And maybe it’s me averting my eyes from him, from the flicker gaping between him and the lens, that glints the depths of memory in the periscope of his pupils.

The sheet is divided in two, the only one in the album. The man’s gaze is turned away from the tracks. Or maybe is turned to the tracks and beyond them. Like Mother’s look, suddenly torn, in some present out of the blue. Maybe I didn’t fold the clothes in the closet and she was struck with anger. Maybe she scrambled an egg, and the movement took her back to an egg she had stirred in secret to sneak it into the ghetto for Marek. The egg stirred in sugar, a “goggle moggle” that didn’t protect him from the arms that pushed him into the childrens’ truck to Auschwitz. Her eyes gaping like the maw of a volcano. Emitting such soft lava.

The man’s look is averted from the tracks. Like the look of Mother guiding me to her on roundabout roads, in my late wanderings on the tracks leading to a nowhere, that doesn’t hold memory. And yet they order me to go on wandering, with a tyrannical command, since the womb, stamped in all of us children of survivors. In each one separately, in the absolute solitude of fate. And yet, in an annihilating similarity, which, against our will, imprisons us together, again.

The obsessive attraction again and again, there, in the seed, to struggle against evil. To try to uproot it from the world, from myself. Until the self is destroyed. The impulse to steal from the beating jaws of trains in the mists of Europe, the eyes of the silent man in the picture, the eternally gaping look of Mother, the pounding of the heart rising in thought of you:

Can’t you see that I am carried to you on a sea of death

not on the Styx – that noble river in a marble Inferno

No Charon leads the raft

On my cheeks still lie the curls of the brother

in whose death I live

His breath is the wind in my hair

Can’t you hear, in our throats’ echoes, the silence

the cry that does not relent, does not release –

of the heads

from whose number a hand was left

to knead our livesCan’t you see

From “That Very Hour.”

lining up behind our faces

the trains that have carried us

on a journey ordained from then and there

Their whistle is our canopy

a pillar of smoke leading us

to the far ends of the wind

Translated from the Hebrew by the author, with Peter Cole; Partisan Review, April 2001.

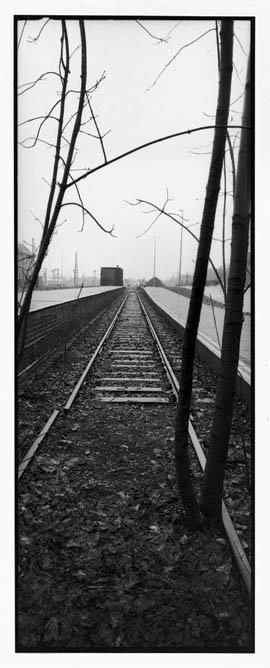

[3]

After a night flight from San Francisco to Sydney, getting on the plane from Sydney to Melbourne, on the service cart in first class – a pile of newspapers. Banner headline: “Explosion in a Jerusalem Pizzeria, Fifteen Dead, Dozens Wounded.” “No, ma’am, you can’t take a paper, they’re only for first class passengers.” Instead of shrieking, I turn my “Aryan” smile on the flight attendant, the smile that has won me preferential treatment throughout the trip to “white Australia,” camouflaging the tremor, “I’ll just stand here a moment to read.” “Please,” he replies at once, probably thinking I want to catch up on some sports news or economic news. And standing, as the stream of passengers passes by me, petrified, I scan the words. Until the photo: a girl on a stretcher, dripping blood. That’s…!” My eyes are covered in darkness. But, no, the girl shouting in pain on the stretcher, she’s not my older daughter’s best friend, she just “looks like her…” The crew turns me around again with that special effort, suggesting I move to first class, not recognizing that I’m “one of them, the marked ones.” The plane takes off, the ground has already dropped off beneath me.

In Melbourne, in the customs line. An official helps me complete the details I filled out distractedly. And jokes. At last, before I take the Israeli passport back from him, he adds, “toda raba,” in Hebrew! And there, in the customs line, in front of the Jewish official, I broke down. The blond disguise falls away, I whisper to him in a choked voice: “Awful news this morning…” “I haven’t read the paper yet,” “Explosion in Jerusalem,” “How awful…” His face falls as I passed by him in the double border crossing. The open one is that of the Australian authorities, and the hidden one, is of Exile. This eternally virginal border, not cut off with seals and passports.

On the flight from Melbourne to Tasmania. Assimilate into the distances? Or, maybe like the remnants of the Ten Tribes, to be absorbed among the Aborigines, until the next Exile, not by the Babylonians, the Romans, the Arabs, the Christians, or the Turks, but by the shipments of prisoners from Britain, in a continuing story of natives and colonizers. I look at the staged, provocative picture of the cooking class in Johannesburg. Look for a long time at the smile of Brenda, brimming with the softness of Yiddish or Polish. See her a little confused from the long time it took to prepare the composition before the picture was taken. Maybe she tried to arrange a place to hold the class in the congregation’s bridge club, or in the synagogue sanctuary, and it didn’t work out. Somebody told her that the old hunting lodge was available. So, what can you do? She smiles in embarrassment, tries to look good – after all the famous photographer from Paris is taking a picture of her business. And at the same time, in my mind’s ear, I can hear Frederic chuckling at the decor of the stuffed deer, zebra and giraffe and the buffalo horns in the foreground. I hear him formulating in his head the judgment on the Jews, like hunters, perpetuating Apartheid, forcing black women to cook Jewish food…

Then I remember the joke about the kosher restaurant in New York, where the Chinese waiter serves gefilte fish and chicken soup, and speaks fluent Yiddish. The Jewish customer doesn’t believe his ears. He runs to the owner and exclaims in amazement: “How did you find a Chinese who speaks such Yiddish?!” “Shhh!,” the owner silences him. “He’s sure he’s speaking English.”

What rises in me at this amazing photo? And from the other side of the joke? The ancient female lesson of “the Jewish gestures,” on the kneading block, at the sink. The first lesson in distinctions. Separating meat and milk, spreading grains of salt to absorb the blood from the meat. Stirring and kneading and grinding and spicing and sprinkling. Every act of cunning work of the “Jewish taste,” dipped in the tastes of the place of Exile and distinct from them.

Everything that generations of Gentile cooks absorbed in Jewish kitchens. The smells, the tastes, the rhythms of the year. Cleaning the hometz, covering the Passover dishes with white cloth towels before the holiday, frying latkes for Hanukkah in skillets bubbling with oil. Or the haste combined with dread at the last meal before the fast on the eve of Yom Kippur.

Everything those women, mistresses, and cooks, lived, one beside the other. Their groans intertwined. Each one with her own tear that dripped into the soup. Jewish tears, Gentile tears. Stamping with its saltiness their days of hardship, their silent lives.

And everything they passed on, the cooks, to the women, to the children hiding in the kitchen, “with the cook,” in the realm of the women, beyond the boundary of the father’s authority. Folk tales that penetrated their childhood. Stories from Ukraine, or from Baghdad, from the steppes of the Pampas or the black neighborhoods of Capetown.

And what did those Gentile servants do when they came to expel the masters? When they saw their brothers assaulting them? On Kristalnacht, in pogroms, in riots? Did they help them pack in secret, in haste, at night? Did they accompany the family with the pots? Did they watch them from the window? And maybe, like Katerina, in Aharon Appelfeld’s novel, they crossed the border and followed in their footsteps, murmuring wordlessly, “Your people are my people, your kitchen is my kitchen,” adding their fate to the boundaries of the laws of meat and milk?

What is certain is that now, in the choked throat of the slaughter in Jerusalem, on the coming Sabbath eve after two days of flying to Hobart in Tasmania (and the organizers of the festival already apologized that there wouldn’t be kosher food there). What is certain is that I’d give a lot for Brenda to be waiting for me (with or without the stuffed skins of the Australian animals), but with her embarrassed, family smile. And especially with kugel and piroshke, and chicken soup with kreplach made by her or by one of the excellent graduates of her course.

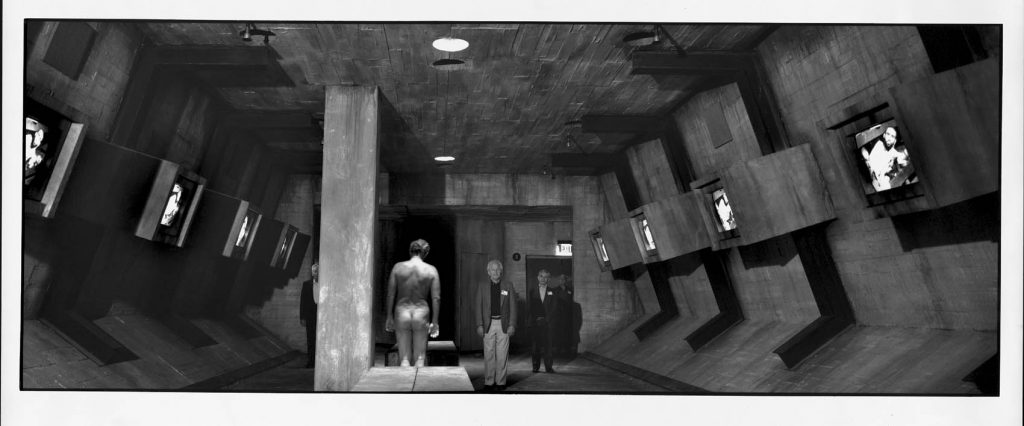

[4]

The hypnotic photo of Moses Elias. In that hallucinatory interior, an Iraqi luxury that went into exile with him to Calcutta.

I look at it on the Sabbath in Hobart. From here, the ferries sail off to the icy expanses of Antarctica. “Edge of the world.” Far away. Like the joke about the Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe who meet in Cafe Flor in Montparnasse. One of them bursts into the cafe and declares happily: “I got a visa!” “Where to?” ask the customers. “Argentina!” he rejoices. “So far away…” they dismiss him. “Far from what?” he asks in amazement.

“So far away?” I responded when I received the invitation to the “Festival of Writers and Readers” in Tasmania. “Far from what?” came the slap in May, when my invitation was rescinded and was renewed only after the intervention of the State Premier of Tasmania and a media attack. Even in distant Tasmania, there’s anti-Semitism, in its current anti-Israeli metamorphosis, I discovered. The war that burst on the ruins of the peace talks, is told in a new version of the ancient terms of blood libel, of deicide, the massacre of the innocents. My invitation canceled “to express horror at the killing of children in the Middle East,” And right away, imposing on me the “Israeli” yellow patch, with a gesture of de-humanization, of the obliteration of every right to a unique identity, a personal literary voice. But only when I got there did I understand the magnitude of the jolt that gripped the tiny Jewish community.

There are few Jews in Hobart, who were exiled here from other exiles, like Moses Elias. Up to now they imagined that the hatred hadn’t wandered in their wake. They clutched the synagogue, the source of their pride, like a buoy. “One of the most ancient in the southern hemisphere,” as the printed pamphlet explains. Inaugurated in 1845 to fill the religious needs of Jewish prisoners, who were exiled to a prison island, Van Diemen (before its name was changed to Tasmania). Brought by guards to the synagogue, they were chained to prayer with handcuffs still visible on the wooden benches. Later joined by Jews, wandering in search of a livelihood. They set up the first printing press, the first factory to produce juice, the cafe, first delicatessen. In their wake come the refugees, Holocaust survivors. Bringing with them the remnants of the last Exile.

Like Moses Elias, who brings with him from Iraq the interior with ceiling lamps and the table, the easy chair, and slippers, and the featherweight servant holding the tray behind him. Sitting comfortably, among all the easy chairs that wait for receptions that will prove his hold on the new reality, in Calcutta.

The wanderings of Exile. The wanderings of heavy easy chairs, family photos, Torah Scrolls. And the wanderings of hatred. Like another limit around the limit of the Sabbath. Surrounding Moses Elias in his opulent interior in Calcutta. Encircling him wherever he’ll still move – for business, health or historical motives. Whispering the story unfurled in one thread from the same skein. From Jerusalem, from Exile to Exile, to the shores of the southern ocean, on the southern edge of the world.

[5]

Sydney. At the sea. Only here, in the pure light capering on the quay, and the banana slices of the opera building at the end of the bay, do I dare look at the darkness of the photo of the “Gas Chamber Gallery” of the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. To formulate my rage, and that of the photo, too, it seems to me.

But on second glance, is the photo really furious? Maybe the naked man isn’t a mannequin, as I thought, and it’s Frederic who’s trying here to “stage” a “gas chamber”?!…

The choking rises in me. As when I was supposed to step into the Holocaust Museum in Washington, through the “railroad car” smelling of fresh wood to “the route of annihilation.” To “identify,” “to be there.” And then, through the dark setting, to enter the “peep show”: a high ledge you have to lean over to peep at photos spread out below. A documentation of Mengele’s experiments. “The exhibits.” (“The victims,” in the proto-theological jargon of “memory of the Holocaust”). And especially a series of “photographic sequence” of the dwarf. Before, during, after. Through the stages of imposing defects and starvation, to the photo of the skeleton after death. Only the photo of him as a free man, the teacher that he was, isn’t there. Or the photo of the street where he lived, or the school where he taught. He exists only as “an exhibit of Mengele’s experiments.” Humiliated again until his death by every one of those who peep at him. Still exploited – if not for “research” purposes, then to stimulate the activity of the tear ducts in groans of horror, in a burst of sadomasochistic pleasure, the “climax” in the orbit of the didactic visit.

Stage settings of the memory that eternalize the perversity at the root of the public, documented rituals of torture. The crowds thronging around the altar of the victims, in the arenas of torments of martyrdom, in the squares where the Marranos were burned at the stake in the auto-da-fe. The same masses crowd in long lines at the peep shows of museums for remembering the Holocaust and for tolerance. They feed, under the mantel of education, the buried murderous impulse, omnipresent in the human soul.

Only because of the light, gleaming from the waves, do I dare go on turning pages…

What rouses me against this photo, doesn’t let me go? Why is the eye drawn to the arms of the men whose eyes penetrate me? To the numbers (only three, and the fourth?), to what is etched on their skin – not the circumcision stamped on the body for life, but an ordinal number in a line to death? I could have sat for hours with every one of them, listened to their hesitant words, to the silences gathered like tears in their eyes.

Did Frederic unwittingly mark those nameless men again in a “composition” of tattooed arms with clenched fist? Violating the pain etched in their bodies to engrave it on the film? Turning them into a photogenic, marketable property: another “curio” written in skin, like the “tattooed man” in the circus or the vagina of the “Hottentot Venus” in a formaldehyde bottle in the Musee de l’Homme.

And what in the sight is so foreign to me, from the depths of childhood before language, unfamiliar? Never was I terrified when Mother walked with bare arms in a summer dress, never did I turn my eyes away when she took off her blouse in the dressing room at the beach. Never did my glance swoop down to the number tattooed on her at the gates of Auschwitz in the summer of 1944 (when in the streets of Paris, they were already dancing to celebrate the Liberation). Never were my dreams haunted by the number on her arm. Never did I see it. I don’t even know what it was.

It existed only in a description, full of admiration, of my cousin Gila (surely quoted from Tonka, her mother. It was Tonka who smuggled her infant daughter Gila and her parents out of the ghetto, holding onto the bottom of a garbage truck. She got to the Land of Israel with them through war-torn Europe. After her husband, Mother’s older brother, was sent to death, and her oldest son was murdered): “When Rega got to Tel Aviv in ’48, accompanying a childrens’ transport,” Gila tells in an emphatic tone, “the first thing she did was to have plastic surgery to remove the number!”

Instead of a number on her arm, Mother’s uprightness resounded with the refusal to turn into a victim. With amazing freedom. Like the laughter she and her companions managed to preserve in Auschwitz, on the death march, in Bergen-Belsen. Every single day, she went on removing the number from her arm, in a struggle with the ashen details of life. Always upright, like a judge. Not only in the court in Hanover facing a group of attorneys in black robes, whom she rebuked in fluent German. But also in the third-floor apartment in Tel Aviv. Mother, the judge in the corridors of judgment between the kitchen and the bedroom, and the everyday difficulties, and the effort to make a living. Exposing the exhibits of memory by putting the plate on the table, cleaning the dust, in the love of Expressionism, in the songs of Brecht she sang. Dripping the silence of memory like drops of wine on the Seder bowl. Like crumbs of leaven that bear the memory of slavery in Egypt.

Crumbs of leaven, such a wretched symbol – and yet, the most profound form of memory, the most radical I know. Not hidden in dark rooms, in dramatic stagings in museums. But crumbs that penetrate the whole universe, every place. Scatter on the carpet, on the table, between the books, under the bed, as far away as the three rows of wine barrels in the repressed, suppressed cellar of memory. The leaven, the yeast in the dough that is also the evil impulse, Eros. The memory that doesn’t deny the dependence of good on evil. A path of crumbs of leaven through which Mother led me behind her, crumb after crumb.

[6]

Melbourne, Hyatt Hotel. Facing three pictures from Jerusalem.

On the eve of Tesha b’Av this year, before the trip to Australia, I went through Jerusalem to Meah Shearim, to hear the Book of Lamentations. I knew I had an arduous trip in store for me at the end of a year, when destruction is again present in the Land, and I went out to draw strength from what for me is ground water, the well of hidden strength.

For years I’ve come here. Crossing the border of Jaffa Road, and continuing with pounding heart up Strauss Street, Haye Adam Street. Alone, or with the few people with whom I shared the wordless yearning, my heart stirred with love.

For years I’ve sneaked here, to the alleys, the book shops, the doorways of the Study Houses where the voices of children reciting burst out. And the lattices of the Women’s Sections. I Stand there, inundated, wordless. Watching inside and out. Between the limits. A stranger among the women who are dressed differently. A stranger among the men. Not clear which is stranger – the softness of the dense bodies of the women, or of the men, who will never refuse when I approach them and ask them for a book, will eagerly search for it, even if they give it to me with their eyes turned away. As if they knew that they and I hold onto the same book, that they are the book I will go on interpreting. Listening together like the Hassidim in the yard of the Rabbi of Lelov listening to the Hassid interpreting in a hushed and concentrated voice.

For years I have come here on an impulse that has also led me to make my home in Jerusalem. In order to walk in the footsteps of the forefathers I didn’t know. My grandfather, Reb Mordechai Globman, tall, in a hat as modern as the Hebrew on his tongue. My grandfather’s father, Reb Itzik Hayot with his thin, white beard, a Hassid of the Rebbe of Skvir of the dynasty of Chernobyl. Passing by me in their black coats in the alleys of Jerusalem, as they walked here when they came from the Ukraine in the 1920s.

This year, on the eve of Tesha b’Av, I drove to north Jerusalem. Park the car in Meah Shearim. Decide for the first time, after all the years, to look for “my” yard. To whisper aloud the right of the forefathers. “Where is the Chernobyl synagogue?” I asked.

Passers-by in an alley. Always in a hurry. Flying off, like angels with their wings spread. Before the Sabbath begins, or the Kol Nidre prayer, running to bake the “shmura Matzo” between examining and burning the leaven, or rushing from the reading of the Megillah to the Purim meal. “Where is the Chernobyl synagogue?” I ask on the eve of Tesha b’av, Saturday night after the Sabbath, in the dark streets filled with the mincing walk of the cloth shoes. On all sides, bearing mattresses, straw mats, stools to sit on the ground, like mourners.

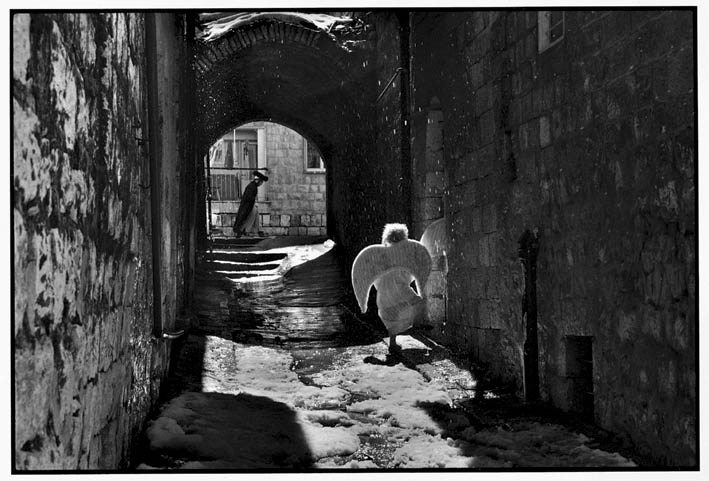

Through the dusty shadows of cedars, I enter the study house, that serves as a Women’s Section. Rows and rows of books, and benches overturned. From the other side of the lattice an old man’s tremulous voice: “How doth the city sit solitary, that was full of people…” And then the spreading whisper of voices, whispering, each in his own distress, “how is she become as a widow! She that was great among the nations…” Around me on the floor a few little girls, the rustle of the silk dresses of full-bodied women, mothers of generations. “I won’t stay until the end of the dirges,” I mutter at the end of the reading of the Book of Lamentations. “Tomorrow I’m traveling.” They nod a kind of Wayfarer’s Prayer. And outside, the moon is almost full and the wind is perfumed, dry, which I’ll take with me on the journey. A negative of memory of a night of Tesha b’Av, and for years I’ll return to its shadows, stealthily, in parentheses. A moment of the fragility of the yearning. Transparent as snow, like a clumsy skip of a little boy dressed up as an angel, and the light hidden in his outspread wings rules for a moment over the whole world.

And maybe it’s not a little boy in the photo, but a little girl. Skipping home in the snow of Purim 1980, in the wake of the wings of her costumed brother. And the neighbor hurrying by, absorbed in his thoughts, an interpretation, or a prayer. Today she’s the mother to seven or ten children, the ones she dresses up for Purim, puts in their hands the pamphlet of dirges and the Book of Lamentations for Tesha b’Av. And in that snow of ’80, at the Purim meal in Jerusalem, when like two strangers my path crossed the path of Frederic who was returning excited from taking this photo in Meah Shearim, I silently identified him as a partner in that community of yearners swallowed up in the arches of gates. Outside, inside. Holding for a split second the wings of the moment spread out, like a new song, like a copperplate of memory that still goes on radiating.

The circles of the dance are revealed to me from the Women’s Section. Rise in my body with the bodies circling one circle after another. The rising foot strikes from the gound, and the soul rises all the way up to heaven. The crowded bodies clasping hand to hand, hand to shoulder, rhythmic stamping, accelerating until the solitary devoted running of the rebbe, and the congregation encourages him, holds.

The dance circles of my grandfather’s father, Reb Itzik Hayot, who ascended to Jerusalem in his old age. Completes the wandering of the family from Spain, through Berlin and Prague, eastward to the Ukraine. Comes to Meah Shearim, close to the eve of Passover, to the Hornstein Houses, with his wife, “the saintly old lady Glikl.” And there, as the family story has it, he dances all night to bless the redemption, in a melody that has come down through the generations, to the lips of my two daughters, who hum it in their pure voices as the Sabbath leaves, at the time of Havdalah.

The dance circles to devotion, to the spread of ecstasy, to the departure of the soul. With the devotion of casting one’s confidence onto God, like a Sukkah that is all temporary, in an awning burst open to the sun, to the stars, to the clouds of honor, the only ones who protect the wanderings that are renewed year after year. Like the opening of the gates of the estate every seven years, the Sabbatical Year, like the remission of debts, the release of earth. Like submission, body and soul, to the Sabbath pleasure – compared to the boundless estate, the Sukkah of David that falls.

Dancing in circles is poured into my body pressed in the womens’ section. The dancing of the submissive men in the softness of the silken rustle, in the drops of heat and sweat. Spinning, soft devotees, like women bearing the seed in the Sukkah of their womb. The dance of the men, clasping one another, spinning with their eyes shut, and the exalted look of the rebbe, “Holy and Awful One save us.”

[7]

Dreams (1)

“And they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.”

“So comrades, come rally/And the last fight let us face/The Internationale unites the human race.”

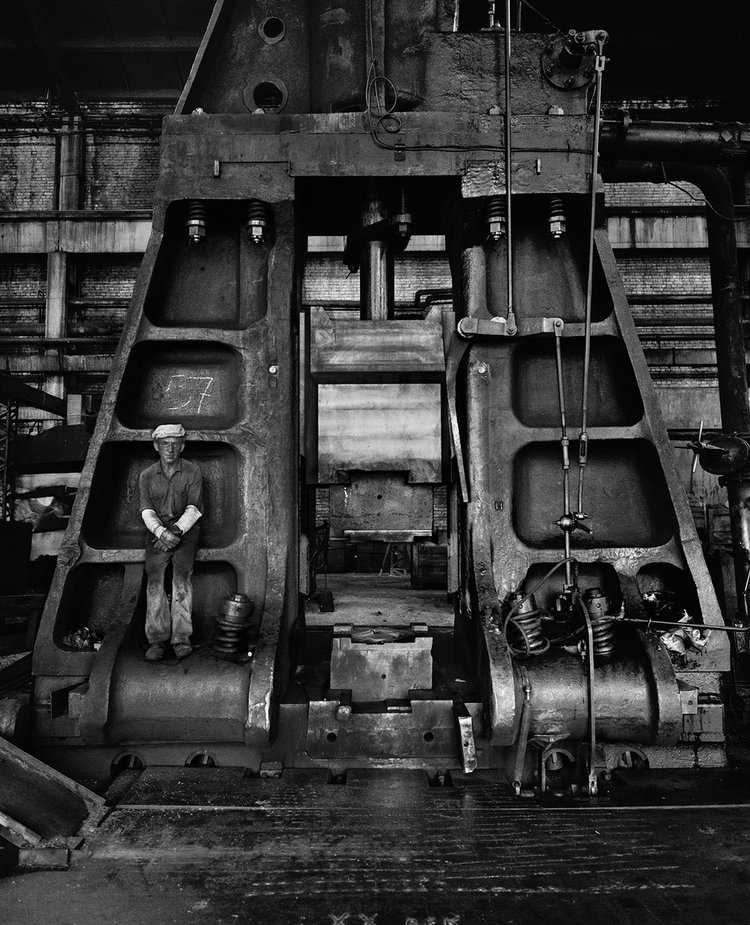

Aleksey Polonkiy sits in the lap of the machine as shy as a Yeshiva student, with the cap of a revolutionary, and his ancient, dreamy eyes. The marvelous photo that won my heart to follow in the footsteps of Frederic Brenner, the footsteps of the melancholy smile of Alexey Polonkiy. One dreamer in the footsteps of another dreamer.

And the dream of the pioneers in the Jezreel Valley, in the 1920s. With the same cap and the singing of the “Internationale” intertwined with the words: “The hands of our forgiven brothers will be made strong and fair/By the dust of our land when they are there; Do not lose your spirit of elation/Come stand shoulder to shoulder with the nation.” And with them the boundless dreamers, led by Elkind, who weren’t satisfied with redeeming the nation, and returned from the fields of the Jezreel to the Soviet Union to redeem the workers of the whole world. Founders of the Jewish Kolkhoz in the Crimea, builders of the Jewish republic in Birobidzan, until they were silenced, and oppressed, sent to punishment camps, to be killed.

A fragment of a dream still flickering in Aleksey Polonkiy’s soft-as-steel glance. From the corner of the machine, the corner of the republic of the dream of human freedom, which remains only as a tombstone in the twenty-first century. When, day and night, the slaves of the Third World create the dreams of advertising, still enslaved to the global economy. Far from Aleksey Polonkiy, far from the dream that once throbbed in Bironidzan.

And I, in the heart of the war between two nations over the same strip of land, between entwined opposed tales of Exile and redemption. I with my dreams of release. Release of property, release of debts, release of slaves. Of opening the fences of the estate to my brothers, to the poor of thy people, to the stranger, to the beast of the field. And the words of the Prophet as a distant dream are still on our lips. “Neither shall they learn war any more.” And the iron steamroller of hatred threatening as always to smash the dreams.

Dreams (2)

…Sabbath afternoon in Cochin, solid circle of heat

From poems of India, in Gufi milim, Ha-Kibbutz Ha-Meuchad, 1991.

on entrance steps painted purple

women smelling of ginger with loin beads

resting between morning and afternoon prayers

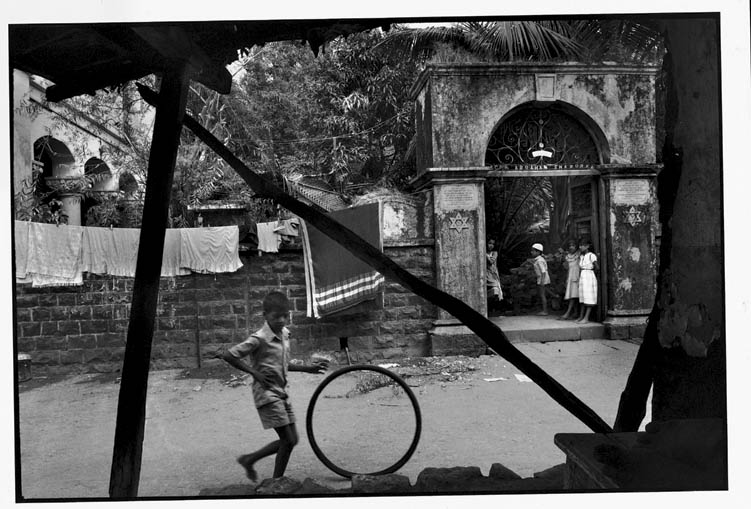

And in the photo from Alibag, who is the little boy rolling the hoop in the foreground of the picture? A Jew, a member of the congregation, or an Indian boy? Drawn to the other children in the doorway with the Star of David on its lintels. Framing the street by rolling the circle. Crossing for a moment tale on tale. For a split second of parenthesis, the time of the shutter opening.

Melbourne. In the hotel club, a jazz group is playing, “Summertime” by Gershwin (Gershovitz) in the island of immigrants. The virtuoso pianist is a short Jew, the drummer a bald Brit, the female bass player is from Vietnam, and the singer, who dissolves the rhythm in a soprano, is from Hong Kong. “Summertime” exiled from Second Avenue to Australia, passing by the Hassids and the Yeshivas, and the echoes of the Holocaust and the tones of Yiddish in the Jewish neighborhood of Saint Kilda in Melbourne. “Summertime” echoes on the continent whose past is buried in the silence of the Aborigines and whose future is written in rejected refugee boats turned away day after day from the shores to the heart of the sea.

“Summertime” in August – winter here. In the cycle of the seasons. Spinning like the hoop of fate, like the egg of mourners. Like the dead rolling in tunnels from Exile to redemption. Like a hoop in the hand of a boy, when it slips away from the plate of the present, to parentheses of dreams of redemption.

At night the drum beat from the temples goes on

From poems of India, in Gufi milim, Ha-Kibbutz Ha-Meuchad, 1991.

Actors with green-painted faces

Dance the tales of the god

A little girl in the street of the Jews wakes up from her sleep

On her bed she calculates the beats

Maybe the sign has come for the End of Days

Notes:

- From Avoth, in: “That Very Hour”, Sifriat Po’alim, 1981. Written in the early 1970s when I “escaped” from Tel Aviv to Paris to study, but also to get away. And precisely in the distance of Exile did the Jewish ground gape under my sky, and from then on I have gone backward, on a well of Exile and Redemption.