Translated and directed by: Michal Govrin

Set: Moshe Sternfeld

Costumes: Genia Malkin

Music: Josef Tal

Lighting: Michael Lieberman

The Cast:

Leon: Shmuel Segal

Helen: Rachel Shor

Simone: Dalia Friedland

Madame Laurence: Ada Tal

Giselle: Yael Druianov

Marie: Miki Kam

Mimi: Adi Lev

First Presser: Rolf Brin

Jean, Second Presser: Itzik Saidoff

Max: Misha Natan

Boy: Shlomi Almagor, Roni Chen, Dekel Granit, Boaz Perlman

Song: Rene Mokdi

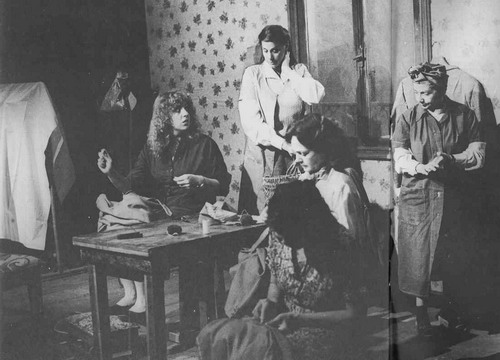

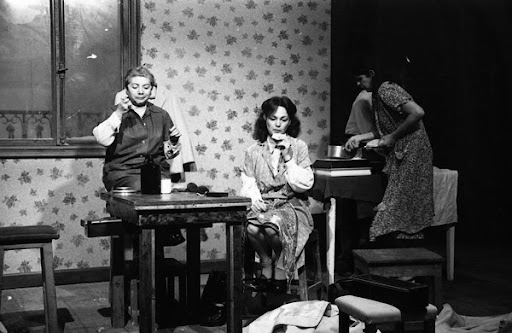

The play takes place in the centre of Paris, in the workroom of a confectionery owned by Jewish Eastern-European immigrants, during the years 1945-1952, immediately following World War II. It begins at the end of winter, a few months after the liberation of Paris. Leon and Helen have reopened the workroom a short time previously, and now employ Madame Laurence; the policeman’s wife, Giselle, a character who seems to have stepped out of the pages of an Emile Zola novel; Mimi, a bubbly, Parisian young woman; and Marie, full of youth and laughter, who dreams only of marrying and settling down.

In the morning in which the play begins, Simone joins the workroom. She is a French Jew taking care of her two young children single-handedly after her husband, “lacking citizenship of Romanian origin”, was sent to the death camps in 1943. Yet life goes on in the world: Marie marries and becomes pregnant; Madame Laurence accepts things as they are; Giselle grows older and older, and Mimi does her best to seize the day. At the same time, the Jews go on struggling to piece back together the fragments of their ruptured lives. They try, unsuccessfully, to mend the tear that has formed between them and the society they have found refuge in. Simone does not accept her fate: for years she waits for the return of her husband from the death camps, until, in a dialogue full of tenderness, the first presser, a survivor of the camps, shatters her hopes.

At the end of the play, in 1952, Europe is heading towards a new future. Small workrooms have turned into large concerns that export their products to all of Western Europe. The times of austerity are over; times of abundance have begun. Life has resumed its regular course, or as Leon puts it: “Everything is so all right everywhere. It is no longer the postwar years, it is again the prewar years. Everything is back to normal.”

But under the paper-thin coating of the new life, the repressed wounds have never healed. Helen has only externalized and hardened her guilt, her pain, her barrenness. The first presser has left without explaining. The “professional” argument between Leon and Max, the marketer, is interrupted by hallucinations that lie somewhere between madness and clear vision of insane reality. And then a boy enters the stage, Simone’s son, who has come to announce that his mother is in hospital.

The ending of the play is not an end. The child who closes the play will live its continuation along with the many questions left unanswered. In his special warmth and humour, Jean Claude Grumberg, who might be that child, tries to mediate between the vast scaled histories and man, who is imprisoned in his contemporary and conflict-filled reality.

On the Jews of France

On June 14th 1940, the German army entered Paris and declared it a demilitarized city. In October 1940 the “Jew Regulations” were decreed, creating restrictions on their occupations in sensitive professions and in the service of the state. Some Jews left for the United States and some, such as joined De Gaulle’s Free France movement in London ((למשל, רניי קאסן וגאסון פאלבסקי. The Jews of Paris were the first to join the underground movement: Fransis Cohen, Susan דג’יאן and Bernard Kirschen were of the organizers of the Student March) on November 11th, 1940, the first protest demonstration in Paris. Foreign Jews, including the Jews of the Baden district who were exiled from Germany to France, were imprisoned in camps in severe conditions. All Jews were forced to organize under German supervision in the “General Union of the Jews of France” (איגוד כללי של יהודי צרפת). In the middle of May 1941 the first of the foreign Jews (some 5,000 people) were exiled; in August another 8,000 and in December roughly a hundred intellectuals.

On July 16, 1942, 12,884 Jews, including 4,000 children, were captured in Paris. During the war, 85,000

Jews were sent from France to the death camps in the east, more than half of them Parisians. Dozens of Jews died in the uprising in Paris in August 1944. In 1956 a memorial to the Jews who perished in the Holocaust was established in the middle of Paris, as part of the “Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation.”