Introduction

I would like to thank Prof. Saul Friedlander for his bountiful lecture and to personally thank him for agreeing to come as the guest of the Transmitted Memory and Fiction group. This is a unique research group comprising artists, scholars, and researchers, and I would like to take this opportunity to thank Prof. Gabi Motzkin and the entire staff of the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute for opening the Institute’s doors to us. Thanks also to Dr. Yochi Fischer, the head of the Institute’s Advanced Studies Unit, for her mentoring.

For decades, Prof. Friedlander’s admirable work starting with his early publications has offered each of us – Including me – challenges, insights, and questions. He continues to do so in his lecture here today. His work is unusual in that it includes the voice of the distinguished historian and attentiveness to the voice of the individual; and throughout, we also keep hearing traces of the voice of the boy who survived. In the brief time allotted for my response I will speak in my own diction, using the point of view and language of literature.

Between Personal and Collective Memory: The Problem of Uniqueness from an Author’s Perspective

My first encounter with the transmission of memory was tangible. As a child I would touch the soft skin of the scar on my mother’s arm. But only after her death did I hear from her family about the operation she had had upon coming to Israel in 1948 that removed the number from her arm. What was her motive? Shame? Pride? The refusal to bear the imposed identity of a victim? A struggle for freedom? Or perhaps the desire to be absorbed in a society in which there was no place for survivors, as we have just heard? Was it the drive to conceal her personal tragedy with the scab of silence in order to begin a new life? And indeed, she spoke with exaltation about the collective and she found meaning for her life in the Zionist dream of building the state, and later in the dream of peace. For her, these were the scaffolds on which to build a new life.

Collective memory, as he emphasized, is an unavoidable social need, but in this case, let me add, it is also unavoidable because of the nature of the event itself. It would not have taken place if not for the plan to exterminate the totality of the collective identity. Each of the victims experienced it as a collective event, and later as well, the strength of the individual to survive and build a new life derived to a great extent from being part of a collective tragedy.

Today Saul Friedlander distinguished between processes of forming collective memory and the uncontrolled and multifaceted eruption of personal memory.

But how can one distinguish between the individual and the collective in my mother’s story and in the stories of other survivors?

In Saul Friedlander’s two-part monumental work Nazi Germany and the Jews he decries the discourse of historians that again and again erases the individual and he makes a key contribution to restoring the voice of the individual victim. And yet, here he broached the question of writing the collective memory. Collective memory, as he emphasized, is an unavoidable social need, but in this case, let me add, it is also unavoidable because of the nature of the event itself. It would not have taken place if not for the plan to exterminate the totality of the collective identity. Each of the victims experienced it as a collective event, and later as well, the strength of the individual to survive and build a new life derived to a great extent from being part of a collective tragedy.

But the intricate relations between the individual and the collective do not end here.

Through my mother’s charged silence – that muteness that Friedlander has talked about in his more personal book, When Memory Comes – my most complex inner childhood experiences were engraved on me. Experiences that are the very roots of my personality. However, with the passage of time, when I set forth to seek what lay hidden behind the wall of silence, I discovered that what I had imagined as my personal, and most secret, story was actually a “cut and paste” of the experience of tens of thousands of other children of survivors.

Literature is indeed committed first and foremost to the voice and fate of the individual, and through them it touches the universal. However, this fundamental distinction was erased from the start by the Nazis’ Final Solution; the Jew as an individual was ground up in the faceless collective identity – “the Jew as the über-threat” – was a stage in the dehumanization process, until he became, in Nazi jargon, a “piece” on the conveyor belt of industrial extermination and recycling of its remains. In the wake of that anomalous event, literature too faces a unique challenge, which lies in the constant tension between the personal and the collective – a relationship whose depths have not yet been sufficiently articulated.

A story that goes beyond the “I,” that transforms the collective into a character and the complexity of events into a story, is, as we know, a myth Hayden White, in his discussion of this new historiography, quotes T.S. Eliot, who claimed that to contend with the complexity of modernity and to give it shape, literature needs to turn from the “realistic mode” to use of the “mythic mode,” that very literary mode that portrays the individual within a supra-personal plot. In his outstanding work, Friedlander pushes the boundaries of historiography and of the omniscient voice of the historian with a huge polyphonic mosaic of testimonies. In thus he suggests another composition of a commanding “plot” and of the individual story. And I will return to this idea at the end of my remarks.

Jewish-Israeli Memory and the Memory of Nations

But, before I respond to Friedlander’s analysis of the incarnations of the Holocaust myth in Israeli culture I must ask, who is writing the myth? In which language? Who are its heroes and who its intended audience, and above all, who is it directed at?

In my search for words that went beyond my mother’s silence, I arrived in Hannover to meet the person who had been the young prosecutor at the trial in which she had testified at the end of the 1970s. In the many hours of conversation with Georg Kröning in 2004 who had meanwhile become a chief prosecutor and who had written dozens of indictments against German citizens who had been exposed as former Nazis, I understood that I was meeting the “witness of the witnesses.” His thoughts about memory and forgetting were unsettling. At the end of one of his thoughtful silences he turned to me and said, “I admire the survivors. From them I received the most important life lesson. What a pity,” he continued, “that the story of their strength to continue and live has not become known to all humankind. How tragic that their lesson was covered over immediately by the conflict in the Middle East and thus was not heard.”

In his research, Friedlander has taught us that the destruction of the Jews was at the heart of the European experience and of world experience, and in his words today, before speaking about the collective Israeli memory, he spoke about the shaping of the memory of World War I in Europe. And if that is how it was in the past, I ask whether the shaping of the Jewish and Israeli memory can be detached from general memory-shaping processes and whether it can continue to close itself off in the Israeli-Jewish “ghetto.” Can it ignore the interests that shape the memory of nations or evade the responsibility of taking part in shaping it?

This is the story of humankind. And the theological dimension of evil was not revealed by divine acts of by forces of nature but rather by human behavior. And therefore, the myth that will contend with the Holocaust must include both the theological and the human.

Memory and the Writing of a Myth: The Face of Evil

I will now focus in this brief presentation on the question with which Saul Friedlander ended his lecture, calling upon us to understand the nature of evil. I will link it to the central question in his lecture, concerning the shaping of the myth of memory. How, then, will this shaping meet the need to confront the face of evil?

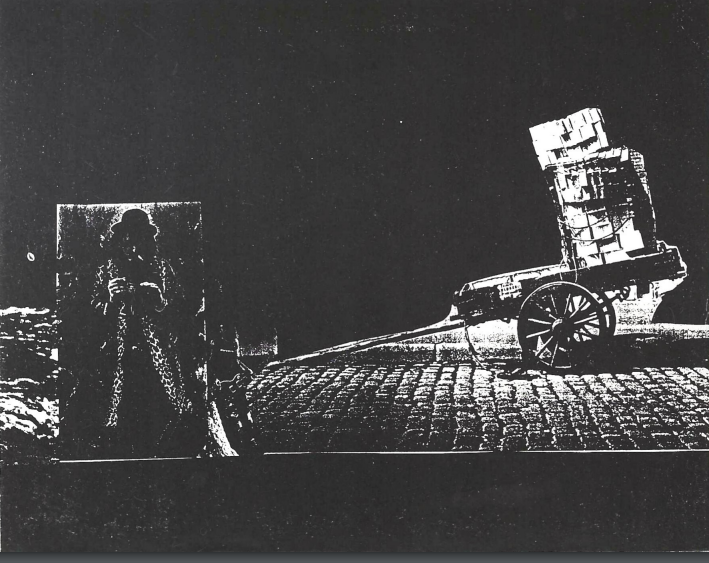

In his groundbreaking book Kitsch and Death, Friedlander presented a courageous and piercing analysis of the fascination with Nazism’s apocalyptic destruction, and primarily the stubborn appearance of its reincarnations – in ambiguous cultural expressions that fall prey to nostalgia or to renewed enchantment with the hypnotic music of death of the Pied Piper of Hamlin. This is a “must” read for every cultured person and an essential guide for the artist who seeks to confront what in another context I called “the theatrical dimension of the extermination process.” The resonance of that ambiguity is not absent from many instances of the shaping of memory, even in the Auschwitz Museum, which could be viewed as what I called, a commemoration of the genius of evil.

In my own experience, evil remains a bald threat that arouses the instinct to flee – accompanied by all the symptoms of claustrophobia when the escape route is blocked. And at the same time there is an attraction, not to evil, but to the struggle against it. That, too, is ingrained in me. That, too, was certainly passed down to me as a legacy. And so too did I inherit indirectly – in the same kind of body-to-body struggle until dawn as took place between Jacob and the angel in the ford of the Jabbok – the wound, the sign that was carved in the flesh.

If evil is an inseparable part of the Holocaust, we cannot escape it by shaping memory to exclude it. However, in contrast to Camus’s novel The Plague, which deals powerfully with a host of responses to evil but in which the root of evil remains as a supra-human factor, a force majeure, biological – a plague – the Holocaust was the revelation of the evil within humankind. The catastrophic conjunction of the complex urges of human beings. This is the story of humankind. And the theological dimension of evil was not revealed by divine acts of by forces of nature but rather by human behavior. And therefore, the myth that will contend with the Holocaust must include both the theological and the human.

The Lurian Myth and Evil

In 1941 and 1942 two Jerusalem scholars, a student and his teacher, publish essays about evil. On the eve of the war, Yeshayahu Tishbi is completing his master’s thesis titled “The Theory of Evil and the Shell in the Kabbalah of Ha’ari [Isaac Luria],” under the supervision of Gershom Scholem. The second edition of the book based on this thesis, published in the 1980s, contains a double dedication, shocking in its terseness. The dedication from 1941-1942 reads, “To father and mother who are imprisoned in Satan’s kingdom and are awaiting imminent redemption,” and under it, the dedication from 1983-1984 reads, “In memory of father and mother who were imprisoned in Satan’s kingdom and awaited imminent redemption.” In 1941, Scholem’s book Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism is published in New York, and it is dedicated as a eulogy to Walter Benjamin. Poignantly, at the conclusion of their correspondence, on the eve of Benjamin’s flight from occupied Paris and his suicide in Portbou, he encouraged Scholem, who was embarrassed to be continuing his research on this very book in light of what was happening in Europe, to continue his work.

Each of the two studies involves a confrontation – that is clearly not detached from the moment of writing – with the question of evil. As Tishbi writes, according to Luria and Ibn Tabul, his disciple – and not as in earlier Jewish expressions, including those of the mystical tradition, where evil was conceived of as an alien force, outside the divinity – the existence of evil is an inseparable part of the Creation and of the divinity, from the very beginning. Evil is implanted as an ancient dualism in the very heart of the divinity as a tool for running the world. But here the myth flips over and opens up in a unique manner to the dimension of human freedom. Evil does exist, starting with the process of tzimtzum (withdrawal or retreat of God) and shvirat hakelim (the breaking of the vessels). But precisely this process that enables the world’s existence also allows the continuation of the process of creation by humankind, from within the existing world and by means of human acts of tikkun (healing). Thus, the myth leads beyond the struggle between good and evil to the cathartic.

Even if we remove the dimension of faith from the Lurian myth, at its heart is the recognition of evil and the responsibility of humankind for the struggle against it. (It is thus perhaps not surprising that a German artist like Anselm Kiefer turns this myth into a tool for struggling in his works against the Nazi myth.)

The threat of enslavement to spiritual or physical destruction hangs over every person; each person, on whichever side of the event, can say, “let every person see himself or herself as if they went out of Auschwitz.” He or she is the person who is responsible here and now for getting rid of the crumbs.

Writing the Collective Memory as a Myth of Vitality

I will conclude by relating briefly to the metamorphoses of the mythic forms of Israeli memory, which Friedlander presented to us. Surely one could also add other, more recent metamorphoses of the memory in new, contemporary forms, in accordance with changing interests. Yet, here I want to emphasize Friedlander’s core statement about the role of the myth of memory as a legitimate means for increasing the nation’s strength. And therefore, the poignancy of the question, which myth will be shaped?

Will it be “Holocaust and Heroism,” with the militaristic context of this mythical approach? “From destruction to redemption,” or “From destruction to revival”? Both are mythical plots that resonate in the Jewish myth leading from the traumatic Temple’s destruction to a messianic yearning for redemption. (And I will not discuss here the complexity of connotations it entails). I will describe these myths briefly, like the entire Zionist myth, as deriving from destruction and exile and leading through struggle to salvation, yet evil is essentially lacking from the horizon of their messianic hope. Therefore, they are all woven into plots with a linear teleological direction, which leads only to an absolute realization lacking any relativity. And therefore, every appearance of a defect in the realization destroys the basis for the mythical line and casts it into the depths of catastrophic despair. In the political context, these deviations from the linear messianic motion are cast in visions of future destruction and doom, couched alternately in terms of left or right, and often relying on victimization and its sanctification.

In conclusion, I will propose shaping the memory of the Holocaust on another mythic basis (because, as is well known, new myths are of necessity echoes of deeply ingrained foundations). Perhaps a more appropriate mythic basis, would be the story of the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, from slavery to redemption a mythic mold immediately opens up universal dimensions (as in the Afro-American struggle against slavery) But first and foremost it avoids the nostalgic fixation – whether threatening or attractive – on the traumatic memory and instead turns it into a lever for an ongoing contemporary and individual process, as articulated in the expression, “Each person must consider himself or herself as if they had come out of Egypt.”

The reading of the Hagaddah as an intimate, family, social ritual offers an infinitely varied basis for new interpretations by its readers. Even evil – the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart – is not lacking and constitutes part of the story, and the same is true for the proportionality of the punishment (as, in the Midrash, God chides the angels who sang after the Red Sea closed over the Egyptians: Those I created drown in the sea and you rejoice). This is a ritual that includes the innocent brother and the evil one, and thus it allows memory to contend with evil without glorifying it. Suffering has undergone symbolization as bitter herbs, whereas the struggle against slavery has been shaped as a symbol with an infinite presence: the elimination of the crumbs of leavened bread that are found in each and every corner of our lives. The threat of enslavement to spiritual or physical destruction hangs over every person; each person, on whichever side of the event, can say, “let every person see himself or herself as if they went out of Auschwitz.” He or she is the person who is responsible here and now for getting rid of the crumbs.

What midrashic corpus will fill the mold of this “Hagaddah”? How to compile it in a way that will enable one to choose and echo the individual voices of the testimony givers, or the clarifying voices of the historians, or those of the artists – that is the task that remains for us.

Was it this that my mother meant when in Auschwitz she sang to herself Tchernichovsky’s poem, “Sahki, Sahki,” “Laugh, Laugh I, the dreamer say… laugh because I still believe in mankind and in his powerful spirit”? Is that what she meant when she went to welcome Sadat? No one can imagine her memories and those of the other survivors, but our responsibility to them is to write the memory, as a gift of life, and for all humanity.

*

Thank you, Saul Friedlander, our outstanding guide, a Moses who was rescued from the bulrushes and became, as we walked through the desert, one of the most valued formulators of the path of life and of the Hagaddah of memory.