The space around me is Jerusalem – my city for over twenty years, since I moved here from my hometown, Tel Aviv, returning from my studies in Paris. All these years, still a pilgrim in Jerusalem, I have been exploring its unique space. Breathtakingly beautiful, always surprising, uncontainable, and constantly changing: the changing light of the four winds of its slopes between desert and lush vegetation, the changing seasons, the changing years of rain or drought, and the changing history – imprinted on its landscape.

During the last ten years, Jerusalem’s space has become the focus of my writing Snapshots1, a novel – whose narrator, the woman architect Ilana Tzuriel, is planning a Monument, or rather an “Anti-Monument” for Peace in Jerusalem. Ilana’s fictional project is located in a real place: on the highest hilltop of Jerusalem, The Mount of the Evil Counsel. It is seven minutes drive from my apartment, just outside downtown; yet, it stays as a foreign “enclave,” belonging to another space and time. A bare hilltop, covered with rocks, thistles, wild herbs, broken glass. From time to time a herd of sheep, led by an Arab Shepard, crosses it. On its slope, next to the remains of a Jordanian outpost, stands the ritual bath of the nearby Jewish neighborhood, and on the very top of the hill erupts the communication antenna of the U.N. forces, stationed at the “Governor’s House,” a relic from the British Mandate.

A desolate Hilltop that dominates an incomparable panoramic view of three hundred and sixty degrees. A space intensely layered – topographically, ethnically, politically and textually.2 The Hilltop’s name, The Mount of Evil Counsel, is a quote from the New Testament, and looking northwards it faces the Saint Sepulcher with Jesus’ grave. To this hilltop Abraham and Isaac, with the young men and the donkey who accompanied them, arrived after three days walk, and watched “from afar” Mount Moriah. And from here Celestial Jerusalem was shown to Ezekiel by the Angel. Beyond the Old City walls, constructed by Suleiman the Magnificent, stands the golden dome of The Mosque of Omar, where Mohammed leaped on horseback to heaven.

The famous view to the north crosses the deep valley of Hinnom, also known as Gehennom or “Hell.” At its bottom, springs the Gihon source, the only natural source of water for the city – next to the three thousand year old site of David’s City. A few steps farther are Gethsemane and the old Jewish cemetery on The Mount of Olives, by the Arab village of Sillouan. To the South, the hilltop faces Bethlehem and the truncated Mount of Herodion, with the remains of Herod’s winter palace. From the fountains near Hebron, the first century ce. aqueduct carried water to the Temple. Today Arab villages and Jewish settlements cover the hilltops, up to the Arab village of Zur Bah’r and the Jewish neighborhood of Talpiot. To the West, lay the dense rooftops and greenery of the new city. And to the East gapes the abyss of the Dead Sea, an enduring deep tone. The deepest place on earth, at the bottom of the Afro-Syrian rift, shows like a long crack less then twenty miles away; and beyond it, on the other side of the river Jordan and the Jordanian border, the Moab Mountains hover. A hallucinating décor that gives a sort of supernatural – if not divine – dimension to the place.3

I climb the Hill, watching this complex space changing, year after year, raising the most challenging question about space: What is the space that will make a place for the complexity of otherness; multilayered enough to enable the co-existence of fully distinct “others?”

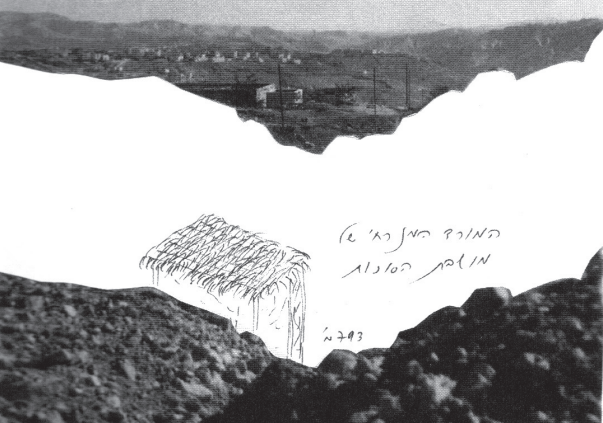

For years I have been attracted to this hilltop – climbing to observe from its heights how the city’s space is changing. During the 80s, a wooden café in a 60s style, “The Shepherds’ Hut,” stood there, just above the last houses of the Arab village of Jabl Muchabr. I used to come here late in the afternoon to have a coffee and write in front of the view. During the first Intifada (1987-1991), it was burned down. In its place a Frontier Patrol shack was built. In the years that followed the Oslo agreement (1993), a delicate balance was maintained among the Jewish neighborhoods, the U.N. base and the surrounding Arab villages, leaving the hilltop for children’s games or shepherds. Tension was in the air, like a transparent frontier of fear mixed with exquisite beauty, always palpable, whenever I parked my car and climbed up the hill with my drafts of Snapshots.

My character, Ilana Tzuriel, planned the Peace Monument for the hilltop as a changing Installation of huts, or Succas – inspired by the intentionally temporary hut that becomes, during the Holiday of Succoth, the dwelling place for Jews – in memory of Exodus and the nation’s wandering in the desert. In Ilana’s project, the visitors-dwellers would study at a “Release Center,” constructed of water and glass, a contemporary interpretation of the laws of “Release” or “Sabbatical Year.” According to these biblical laws (never fully applied), all land, property or debts are liberated every seventh year, during which the land stays fallow, the crops are given freely to all, and fences are knocked down, in a reminder of Man’s inability to own the land, “for the whole earth is Mine” – a notion still poignantly radical in a global market world, or in Jerusalem.

The armed conflict of the Second Intifada broke out in the fall of 2000. For long months Jerusalem has been under siege, with dozens of terrorists’ attacks and suicide bombers leaving hundreds of dead and wounded. The Frontier Patrol shack was turned into an armored post, and on the road coming up from Jabl Muchabr a checkpoint was installed. From Bethlehem the sound of Palestinian Militias firing could be heard – as well as the retaliation of Israeli tanks. My growing pain and rage were mixed with despair. In my last draft of Snapshots, Ilana’s plan was expanded to include a “prophetic” project of rebuilding the ancient water aqueduct that crosses the present zone of fighting from Hebron to Jerusalem. As the war intensified, so did the imaginary flow between The Square of The Mosques to the Saint Sepulcher, in a continuing cascade next to the Western Wall, cutting across borders of holiness and hatred in a gush of life.

I kept sneaking to the hill top. One day I was amazed to discover bulldozers on its slope. A few months later the stunningly beautiful new Promenade, designed by Laurence Halpern, was ready, as if an echo to Snapshots. The Promenade has not been officially inaugurated, because of the danger. Yet, in summer afternoons its paths are visited by Arab children and mothers from Jabl Muchabr, some courageous joggers, and a few strollers.

Once again, these very days, Jerusalem’s space is radically changing. Facing the Hilltop, on the slopes of the Mount of Olives, the construction of the Separation Barrier, known as “The Wall,” advances like a snail, crossing Abu-Dis, reaching southwards. It painfully changes lives. It radically changes the city, the region’s space. It cuts Jerusalem from Bethlehem, from Hebron and from the natural space of the Judean Mountains. It creates a barrier between Arab villages. It condemns to isolation or dismantling Jewish settlements. It separates de facto Israel from Palestine.

A security barrier, replacing the frozen Peace Talks turned into violence. Originally vehemently advocated by the Israeli Left, being built by a right-wing government. Its route, designed to protect as many Jewish neighborhoods as possible, harms the Palestinians. It becomes for a period the galvanizing symbol of the Palestinian Fight for Freedom, and of Anti-barrier demonstrations. It provokes from the International Court of Justice a declaration of its illegality. While a recent ruling of the Israeli Supreme Court judges it legal, but has demanded some changes in its route to make it less onerous for Palestinians.

Is this barrier going to be “The Wall of The Ghetto?” And for whom: for Palestinians or for Israelis? Will it discourage terrorism, and put a border on hatred, or only instigate more frustration and hatred? Does it establish the grounds for a future recognizable border at the end of occupation? Is this barrier the unavoidable stage of separation needed to delineate property, identity, nationhood? Is it a fatal mistake, or is it a means to one day enable the tearing down of barriers and of fences, as in the year of “Release”?

I climb the Hill, watching this complex space changing, year after year, raising the most challenging question about space: What is the space that will make a place for the complexity of otherness; multilayered enough to enable the co-existence of fully distinct “others?” Facing this question will require not less then a global revolution – in the Muslim Jihad’s claims to ownership of the land, in the Christian Western aspirations of dominion over Celestial Jerusalem and terrestrial oil wells, and in the Zionist dream. And maybe there also must be a Jewish dimension of “Release.”

I stand on the Hilltop in the midst of an oppressive present moment. I watch this intense space imprinted with history like an Archive of the layered story of Western civilization, with its heights of belief, love and poetry and its abysses of stupidity, fanaticism, jealousy and cruelty. I stand on the Hilltop, in the midst of this amazingly beautiful arena of nature and mankind, and I cannot resist naming it “outrageous hope.” Another synonym for “Jerusalem.”

August 2004

Notes:

- Michal Govrin, Snapshots (Hevzekim, Am Oved, 2002) translated from the Hebrew by Barbara Harshav, forthcoming in Riverhead Books of Penguin-Putnam, New York. Hevzekim won the 2003 “Best Book of the Year” Akum Award in Israel.

- For a historical-political analysis see: Michal Govrin: ‘Martyrs or Survivors, the Mythical Dimension of the Story War’, Partisan Review, 2003/2.

- For a reading of Jerusalem as a feminine place of desire see: Michal Govrin, The Name, translated from the Hebrew by Barbara Harshav, Riverhead Books of Penguin-Putnam, 1998; And, Michal Govrin, ‘Chant d’outre tombe’, in: Passage des frontières; autour du travail de Jacques Derrida, colloque de Cerisy, Galilée, 1994.