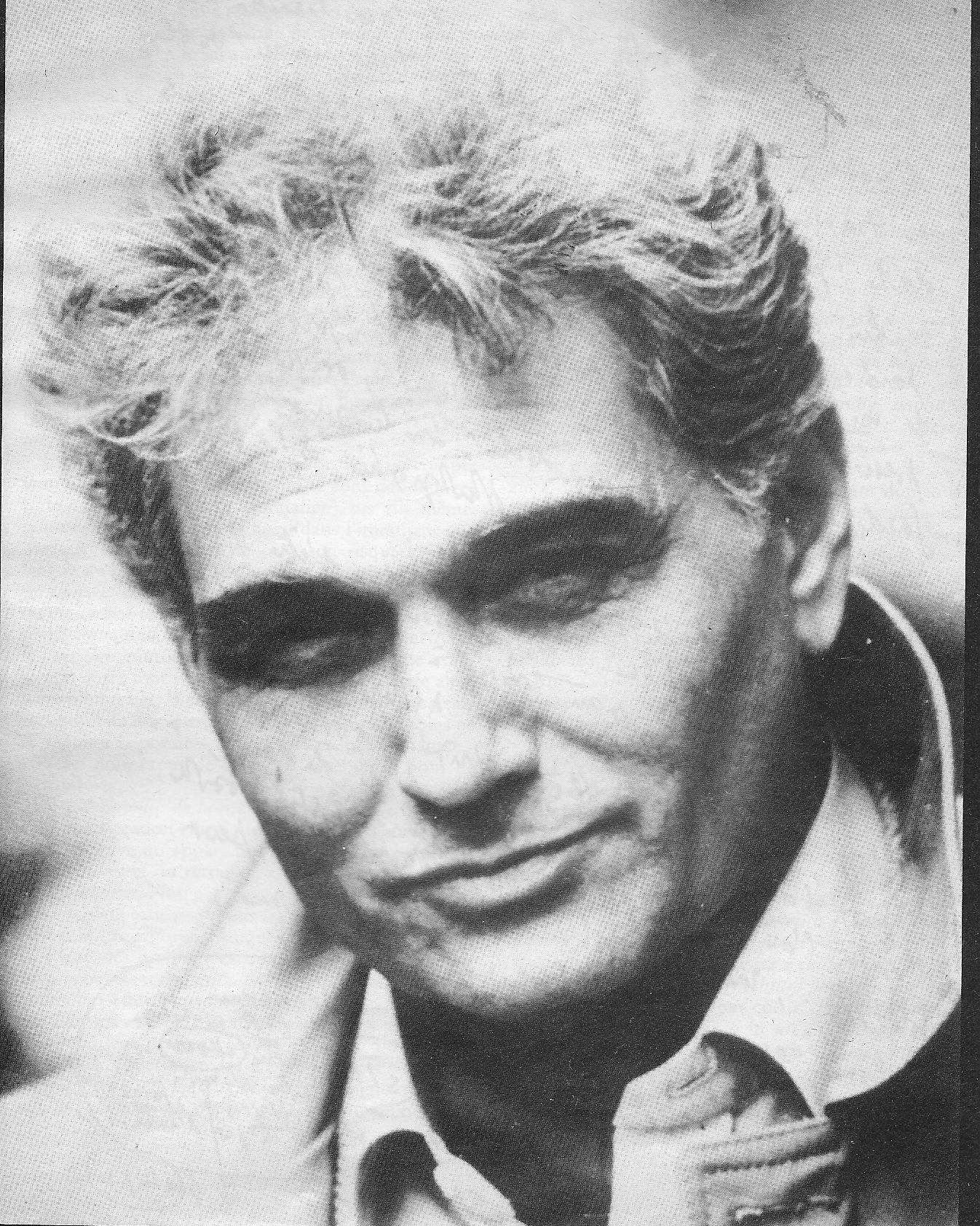

Today Jacques Derrida was buried in Paris. A life story laid to rest, sealed, closed. The end of a life bigger than life, life of perpetual struggle, of deconstruction that did not spare its own inventor, as he testified in the last interview he gave a month before his death: “I am in war against myself, it’s true, you cannot imagine to what extent… I sometimes see this war as a terrifying and painful war, but at the same time I know that that’s life” (Je suis en guerre contre moi-meme, c’est vrai, vous ne pouvez pas savoir a quel point…Cette guerre, je la vois parfois comme une guerre terrifiante et pénible, mais en meme temps je sais que c’est la vie). Life and teaching whose own vitality and the life it gave were engendered by a power of constructing destruction. And relentlessly. “I will only find peace in eternal rest” (Je ne trouverai la paix que dans le repos éternel) he went on saying, and at the next moment contradicted his own words, because “I also know that that’s what keeps me alive” (je sais aussi que c’est ce qui me laisse en vie). Jacques Derrida, one of the greatest voices of the contradiction of existence. Of the mystery of the un-namable difference. Leaving the contradiction open with his death. End-less and without closure.

One the main contradictions of Jacques Derrida’s life was his being a Jew. His being, or his refusal or reluctance to be part of a Jewish “we”. During his life, but not less with his death and burial. Maybe “that which is the most worried in my thinking” (ce qu’il y a de plus inquiet dans ma pensée), as he confessed in this last interview. A tormented existence that “will be in my thinking what Aristotle profoundly say[s] about prayer (eukhé): it is neither true nor false. And this is precisely, literally, a prayer.” (Ce serait dans ma pensée ce qu’Aristote dit profondément de la prière (eukhé): elle n’est ni vraie ni fausse. C’est d’ailleurs, littéralement, une prière.) Prayer: an apparently unexpected topic for a philosopher seen for many years as the banner carrier of radical anti-metaphysics, as the guru of the believers in a materiality devoid of any “au delà”.

Jacques Derrida, one of the greatest voices of the contradiction of existence. Of the mystery of the un-namable difference. Leaving the contradiction open with his death. End-less and without closure. One the main contradictions of Jacques Derrida’s life was his being a Jew.

After the seven or the thirty days of mourning , when the waves of contradictions, that will not subside with Jacques Derrida’s death, will leave the water surface empty of his presence, it will be, maybe, possible to write about the years of friendship between Paris and Jerusalem passing via New York, friendship that returned, every time anew, to prayer. Its words or its place. The hope or the hopelessness it carries, it opens. “I’m thinking of another possibility [of prayer] that I cannot exclude”, he said in our public meditation, joint by the poet David Shapiro, and published in: Shapiro, Govrin, Derrida: Body of Prayer (The Irwin Chanin School of Architecture of the Cooper Union, New York, 2001), “the possibility of a hopeless prayer. You may pray without any reference to the future, just to address the other, hopelessly, hopelessly: in reference only to the past. There is only repetition, no future. And, nevertheless, you pray. Is that possible? To pray hopelessly? And is it possible to pray hopelessly, not only without request, but even by giving up hope? If one agrees that there is such a possibility of prayer, a pure prayer, that is hopeless, then shouldn’t we think that finally the essence of prayer has something to do with this despair, with this hopelessness? The pure prayer doesn’t ask for anything, not even for the future. Now, I can imagine the response to this terrible doubt: that, even in this case, if I pray hopelessly, there is a hope in the prayer. I would hope, at least, for someone sharing my prayer or someone listening to my prayer, or someone understanding my hopelessness and my despair and so in that case there is, nevertheless, a hope and future. But perhaps not, perhaps not. At least perhaps, this is for me also, a terrible condition of the prayer.”

“But perhaps” that was also the life of a friendship which was a call, in a perpetual space of address. A loyal friendship, in spite, or perhaps because of its contradictions – about the “we” – the Jewish or the Israeli “we” – crossing wars and waves of Anti-Semitism, agreeing at moments of despair that at least we agree that we do not agree. Friendship that emerged out of one Hebrew word, opening like an amazing landscape, and continued during a quarter of a century, interpreting the most difficult of words, the most difficult of places: Jerusalem – a place or a call, a contradiction of despair and hope, like a prayer. Friendship that lead to the old Jewish cemetery on Mount of Olives, and followed during Jacques Derrida’s last visit to Jerusalem, for the reception of a Honorary Degree from the Hebrew University, a week after the diagnosis of his terminal disease was made known to him. Then, late at night, after the celebrations and the official events were over, and with an urgency as if this was the only reason for his coming, he asked only for one thing: the go to the Western Wall. At the heart of night, alone, with a body bent in advance with knowledge of the awaiting suffering, he walked towards the lit wall. Not with a Hebrew prayer book, which he was incapable to read, but with a Bible, in French. In a prayer of “perhaps”, of the hopelessness hope of existence. A prayer of a Jew who saw himself, with utmost pride and with utmost despair as “the last Jew”. As if only thus he will pray to the contradictory un-namable, as if only thus he will be a Jew.